I have a big collection of roleplaying games—far too big, I’m reminded every time I venture into the basement room where it resides. With a few exceptions, my collection doesn’t contain anything terribly rare or valuable (the games in my library that would command the highest prices from collectors also happen to be the ones I played to death over the years, so they’re far from mint condition). But I do have a good number of oddities nestled amidst all the predictable D&D tomes. I came across one of them today while rearranging the family bookshelves.

I have a big collection of roleplaying games—far too big, I’m reminded every time I venture into the basement room where it resides. With a few exceptions, my collection doesn’t contain anything terribly rare or valuable (the games in my library that would command the highest prices from collectors also happen to be the ones I played to death over the years, so they’re far from mint condition). But I do have a good number of oddities nestled amidst all the predictable D&D tomes. I came across one of them today while rearranging the family bookshelves.

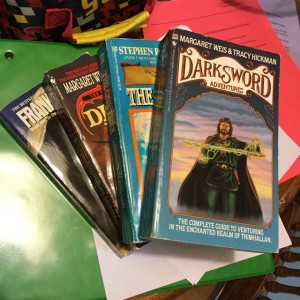

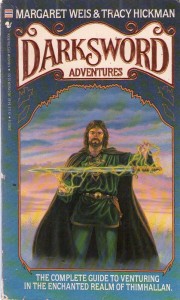

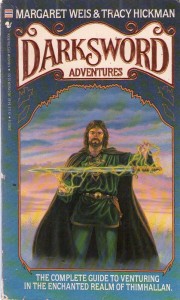

It’s called Darksword Adventures. And it’s an odd duck.

It is not, as far as I can tell, rare or valuable. (The going rate on Amazon for a used copy is one cent.) But in my many years of going to game conventions, lurking on roleplaying game forums, and playing all manner of games, I swear to you I have never once heard Darksword Adventures even mentioned, let alone have I seen evidence that anyone has ever played it.

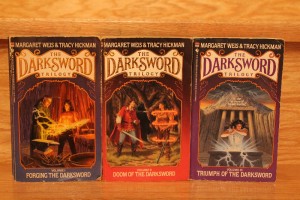

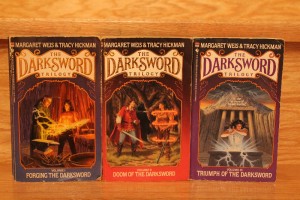

Let’s take a look at this quirky little artifact of gaming history. It’s written by the mass-market-fantasy powerhouse team of Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman, authors of the immensely popular and influential Dragonlance chronicles. Darksword Adventures is a roleplaying game (sort of—more on that in a bit) based on a different fantasy trilogy they wrote in 1988: the (you guessed it) Darksword Trilogy.

The Darksword series is set in a fantasy world called Thimhallan. Its central gimmick is that everyone in Thimhallan is a magician of sorts, able to tap into a Force-like source of magical power and employ it to do things that would otherwise be done with machinery and technology. In fact, mechanical devices and anything (or anyone) that operates on principles other than magic are considered to be “dead” abominations. The hero of the series is a man born “dead”—unable to use magic. There are ancient prophecies, annoying “comic” sidekicks, noble sacrifices, a depressing ending, and other stuff you’d expect from a 1980s fantasy saga. It’s not going to dethrone Tolkien anytime soon, but it was appealing enough for high-school-aged me.

The Darksword series is set in a fantasy world called Thimhallan. Its central gimmick is that everyone in Thimhallan is a magician of sorts, able to tap into a Force-like source of magical power and employ it to do things that would otherwise be done with machinery and technology. In fact, mechanical devices and anything (or anyone) that operates on principles other than magic are considered to be “dead” abominations. The hero of the series is a man born “dead”—unable to use magic. There are ancient prophecies, annoying “comic” sidekicks, noble sacrifices, a depressing ending, and other stuff you’d expect from a 1980s fantasy saga. It’s not going to dethrone Tolkien anytime soon, but it was appealing enough for high-school-aged me.

Anyway. Like most of Weis and Hickman’s numerous non-Dragonlance series, the Darksword novels didn’t catch on like Dragonlance did. But its publisher believed in it enough to publish a truly odd follow-up book: Darksword Adventures, “the complete guide to venturing in the enchanted realm of Thimhallan.”

Why was this book weird, you ask? Because it’s a roleplaying game system disguised as a paperback novel. More specifically:

See? Looks just like every other novel on your 1980s teenage self’s bookshelf.

In the 1980s, roleplaying games were published as oversized, textbook-style tomes or fancy boxed sets.

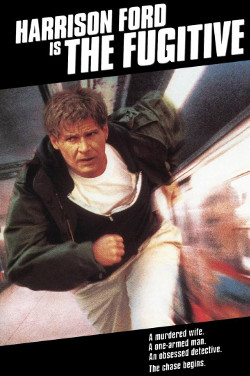

Darksword Adventures, however, looked exactly like a 1980s paperback fantasy novel—physical size, cover art, everything—which presumably let the publisher get it shelved next to all the bestselling Weis/Hickman novels at bookstores rather than relegated to a “games” section in the back of the store. Shelved alongside other mass-market paperbacks, it would be indistinguishable from them at a quick glance. At the time, I’d never seen a full-blown RPG in a paperback-novel format (not counting a few “choose your own adventure” style RPG-lite gamebooks).

It was presented more as a fan guide than as a game. The back-cover copy pitches the book mostly as a fan companion to the Darksword novels, not as a D&D-like roleplaying system. It was clearly an effort to break out of the roleplaying market and entice non-gaming fantasy readers. In later years, companies like Guardians of Order would publish combined fanguide/roleplaying game sourcebooks for various media properties, but in the late 80s I hadn’t seen any such thing before.

The writing is in-character and very ‘meta.’ Every roleplaying game I’d encountered by the late 80s was written like a textbook. The game rules read like a technical manual, and setting descriptions read like an atlas or encyclopedia entry. Darksword Adventures, however, presented both its setting and its rules in the voice of a character from Thimhallan. The setting is described in a (fairly entertaining) novella-length travelogue written by an inhabitant of Thimhallan; the game rules are presented with the in-setting conceit that they’re a popular form of organized make-believe enjoyed by Thimhallans, called “Phantasia.”

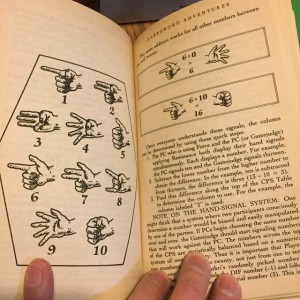

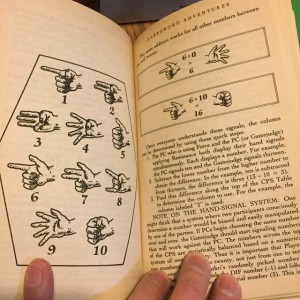

I’m not sure this is any quicker or better than going out and buying some game dice. But I respect the effort.

includes an overly complex, but workable, method for determining random results using hand signals, on the assumption that you might not own nerdy gamer dice. Which was probably a safe assumption if your target audience was not existing RPG players.

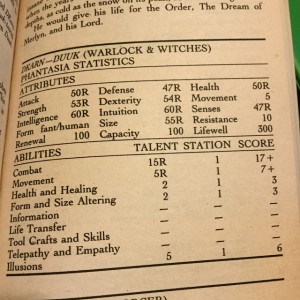

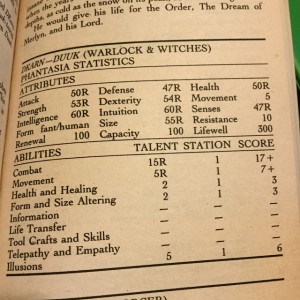

It’s nonetheless a full-blown roleplaying game system. It’s as complete a game system as most of its peers at the time, covering character creation, a big variety of character classes (different varieties of wizard, as you would expect from the setting), a (typical for the 1980s) complicated but logical rules system, a bestiary, a surprisingly interesting and versatile magic system, and enough world information to run a campaign. You just had to get over the fact that much of it is presented in-character.

A character statistics writeup from Darksword Adventures.

While (as far as I can tell) it went almost completely unnoticed by the gaming world,

Darksword Adventures was doing some legitimately interesting things. It was an early attempt to cross over into the (huge) non-gaming, fantasy-reading market. It eschewed most of the telltale formatting and presentation standards of the game publishing industry in order to do so. Its rules and writing style didn’t assume any gaming expertise (or even ownership of dice). I’m sure it wasn’t the first game to attempt most of these, but it has to be one of the first to attempt

all of these things at once.

I have no idea how well it did or didn’t sell, but the complete lack of buzz about the Darksword RPG then or now suggests that this was a failure, albeit a noble one. Since then, many roleplaying games have embraced one or more of the elements above, with varying degrees of success. Darksword Adventures isn’t exactly a lost classic, but for historical reasons at least, it would be fun to see a reprinted or revised version made available again.

by

by

I have a big collection of roleplaying games—far too big, I’m reminded every time I venture into the basement room where it resides. With a few exceptions, my collection doesn’t contain anything terribly rare or valuable (the games in my library that would command the highest prices from collectors also happen to be the ones I played to death over the years, so they’re far from mint condition). But I do have a good number of oddities nestled amidst all the predictable D&D tomes. I came across one of them today while rearranging the family bookshelves.

I have a big collection of roleplaying games—far too big, I’m reminded every time I venture into the basement room where it resides. With a few exceptions, my collection doesn’t contain anything terribly rare or valuable (the games in my library that would command the highest prices from collectors also happen to be the ones I played to death over the years, so they’re far from mint condition). But I do have a good number of oddities nestled amidst all the predictable D&D tomes. I came across one of them today while rearranging the family bookshelves. The Darksword series is set in a fantasy world called Thimhallan. Its central gimmick is that everyone in Thimhallan is a magician of sorts, able to tap into a Force-like source of magical power and employ it to do things that would otherwise be done with machinery and technology. In fact, mechanical devices and anything (or anyone) that operates on principles other than magic are considered to be “dead” abominations. The hero of the series is a man born “dead”—unable to use magic. There are ancient prophecies, annoying “comic” sidekicks, noble sacrifices, a depressing ending, and other stuff you’d expect from a 1980s fantasy saga. It’s not going to dethrone Tolkien anytime soon, but it was appealing enough for high-school-aged me.

The Darksword series is set in a fantasy world called Thimhallan. Its central gimmick is that everyone in Thimhallan is a magician of sorts, able to tap into a Force-like source of magical power and employ it to do things that would otherwise be done with machinery and technology. In fact, mechanical devices and anything (or anyone) that operates on principles other than magic are considered to be “dead” abominations. The hero of the series is a man born “dead”—unable to use magic. There are ancient prophecies, annoying “comic” sidekicks, noble sacrifices, a depressing ending, and other stuff you’d expect from a 1980s fantasy saga. It’s not going to dethrone Tolkien anytime soon, but it was appealing enough for high-school-aged me.