The story: “Bad Little Kid,” collected in The Bazaar of Bad Dreams. First published in 2014 (in German and French, interestingly enough). Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: Throughout his life, George Hallas is visited by an unaging schoolyard bully who appears every few years to murder somebody George holds dear. George eventually contrives to kill this apparently demonic being, but at the cost of his own life: he is convicted and executed for murdering a child. The story’s final pages make it clear that the bully is no figment of George’s imagination.

My thoughts: What would you say is the archetypal Stephen King villain? To be sure, he’s created quite a few classic bad guys, from creepy supernatural entities (Pennywise from It) to psychotic madmen (Jack Torrence from The Shining). But if you ask me, the definitive King villain type is the schoolyard bully.

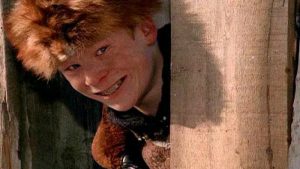

Imagine this guy showing up in your life every few years.

This might seem a little ridiculous at first, and it is a bit jarring when a nightmarish Lovecraftian entity pauses to tease its victims about their asthma. But King knows that horror is more effective when it exploits real-life fears, and who among us hasn’t had some kind of upsetting encounter with bullying behavior? Whether it was getting pushed around on the playground or being ostracized at work, most of us have experienced the humiliation and helpless rage that comes from witnessing, or being victimized by, bullying.

And so here we are with “Bad Little Kid,” a story about an actual, stereotypical schoolyard bully. Throughout all of his life, George Hallas has been terrorized by a non-aging, apparently supernatural child who appears every few years to kill somebody he loves (usually through a sequence of events that can be passed off as a tragic accident). Whether it’s luring George’s best childhood friend into the path of oncoming traffic or harassing his aging nanny with threatening phone calls until she has a heart attack, this very bad little kid has it out for George. (George narrates this story from death row—he ultimately managed to gun down the evil kid, but of course to the rest of the world it looked like he murdered an innocent child in cold blood.)

Two things stand out to me about this story. First is that it’s in many respects a retread of “Sometimes They Come Back,” an early King story also involving ageless, murderous supernatural bullies. Unfortunately, “Bad Little Kid” comes out worse in a comparison between those two stories. In “Sometimes,” the beleagured protagonist devises a truly original way of dealing with the bullies: demon summoning. By contrast, in “Bad Little Kid,” George simply buys a gun and shoots his tormentor. Gunning down your enemy might be the most American way to deal with problems, but from a narrative perspective it’s a lot less interesting than calling on infernal powers.

Second, “Bad Little Kid” allows for some interesting speculation about what’s really going on here… only to dash that ambiguity with a strangely disappointing denouement that reveals the evil bully to be an actual, real demonic being. The story hints at various alternative theories about George’s predicament. It might be that George is inventing the “bad little kid” in a desperate attempt to attach some kind of cosmic rationale to the seemingly meaningless (but natural) deaths of those he loves. Or the “bad little kid” might be a delusional manifestation of George’s own murderous impulses—most of the victims are women with some kind of perceived weakness or vulnerability (disability, mental illness, minority status, etc.) who might have triggered some kind of hidden misogynistic reaction in George. But rather than leave us pleasantly uncertain of the explanation, King settles on what I would say is the least interesting option: the bad little kid is a demon from hell.

This story also gives King a chance to once again articulate what I take to be his own understanding of the “problem of evil.” Asked to explain why the demonic bully chose to pick on him, George retorts:

You might as well ask why one baby is born with a misshapen cornea […] and the next fifty delivered in the same hospital are just fine. Or why a good man leading a decent life is struck down by a brain tumor at thirty and a monster who helped oversee the gas chambers of Dachau can live to be a hundred.

This is a competent story, but it’s overshadowed by many other King works that explore similar ideas. I recommend the cruder, but more compelling, “Sometimes They Come Back” instead.

Next up: Let’s shift gears and read something with a bit more heft: “The Mist,” a novella-length story collected in Skeleton Crew.