In 2020, Free League Publishing released Destroyer of Worlds (DoW), an adventure for their new and well-regarded Alien roleplaying game. It’s the second published adventure for Alien (if you don’t count the short scenario included in the core rulebook).

In contrast to the relatively claustrophobic scale of Chariot of the Gods, the first adventure, DoW is incredibly expansive and action-heavy. That makes it a great purchase for any Alien RPG gamemaster—there’s enough material in here for months of gaming. But ironically, its very “bigness” can be a weakness. There’s simply so much going on in this adventure that it’s tricky to run.

I ran DoW across three game nights (about 10 hours total) and have some advice for other GMs thinking about running it for their Alien game group!

A quick note before we dive in: this isn’t an “is it bad or good?” review of DoW. That kind of review can be found elsewhere online. I really enjoyed running DoW, but after we finished, I knew that if I ever ran it again, I would approach it differently in some specific ways. I hope you find these suggestions helpful, or at least worth considering.

Tip #1: Take your time

As written, DoW is intended to take “at least three sessions to complete.” I’d like to emphasize the “at least” part of that!

There’s a lot to do and encounter in DoW. Running it across three sessions required my group to barrel through extremely complicated situations and encounters at high speed. While keeping the pace does provide some cinematic tension, it also meant that the players didn’t have time to engage with any of the adventure’s events or NPCs in anything but the most superficial way.

My advice is that you plan from the outset to spend at least four, and more probably six, game sessions with DoW. With all of the factions and agendas at play, you could actually make this a full-blown campaign and spends months in it–but 5-6 sessions is a good middle ground between making it a full-fledged sandbox, and ramming the players through it at breakneck speed.

If you know you’ll be spending more time in the setting, you can also be a little more deliberate in introducing some of the many major plot-propelling events that occur regularly throughout DoW. Many of the semi-random events in DoW are designed to close off areas/stories and push the PCs into the next act of the story; they’re a useful way to prevent PCs from noodling around aimlessly and losing track of the plot, but they can also feel like they’re roughly shoving the PCs down the plot pipeline. Take a note of the specific cataclysmic events that seem most interesting to you, and trigger them intentionally at points that fit the pace your game table wants.

Tip #2: Expand the player options to include non-Marine locals

DoW’s setup is that the player characters are Marines sent to track down a band of AWOL soldiers in a mining colony town that is sitting on the brink of collapse (due to an assortment of looming threats). That’s a fine setup that has the virtue of giving the PCs a clear goal and some helpful constraints on their actions.

The downside is that this setup means the PCs arrive on the scene of this collapsing colony with no personal connection to anything that’s going on. But wouldn’t the plot twists and dramatic moments hit harder if the PCs have personal stakes in the colony and its fate?

I highly recommend expanding the player options to include non-Marine locals. Any of the character archetypes in the Alien core rulebook (pages 38-54) would work well. Here are some examples of how you could plug more archetypes into DoW:

Colonial marshal: it makes sense that the colony’s sheriff would accompany or even lead a search for AWOL marines who have disappeared into the colony population. In fact, there’s an NPC marshal in DoW already (p. 26) who could easily be a PC.

Kid: did you like the dramatic elements that Newt brought to Aliens? It’s easy to imagine that in the chaos of the collapsing colony, a clever local kid might wind up in a group of PCs. Maybe they were separated from their family in the evacuation. And maybe they know the secret ins and outs of the colony better than the grown-ups do!

Medic or scientist: there’s a small hospital in the colony staffed by “one doctor, an intern, and a medtech”—those all sound like perfectly viable (and useful) PCs!

Pilot: DoW has a sideplot involving two spaceships that might be escape routes off the planet–one medical frigate and a freighter grounded with a damaged reactor. The freighter’s captain is an NPC who can be found drowning her sorrows in the colony bar. She’d make a good PC, especially if you want to allow for the possibility of the PCs repairing, hijacking, and/or escaping on one of those ships.

Roughneck: the colony is populated by gruff oil refinery workers. One or more might be deputized to help track down the AWOL soldiers, especially if they know the colony and its hiding places well.

Adding just one or two of the above civilian PCs adds a personal connection between the PCs and the doomed colony, and add a lot of roleplaying possibilities. Any of these civilians could have secret agendas of their own—the roughneck oil worker could be a secret communist sympathizer, for example. I highly recommend expanding the PCs to include more than just marines.

One thing to keep in mind, however, is that civilian PCs won’t necessarily have access to all the firepower that marines do. This will obviously affect how they’re able to respond to the inevitable alien outbreak. For this reason, you might want to adjust the types and numbers of aliens in the adventure to accommodate a less-well-armed group of PCs. More on the aliens later!

Tip #3: Focus on just a few major threats and agendas

Trim down the list of factions in play.

Did I say there’s a lot going on in DoW? Let’s take a look at a slightly simplified list of the different groups and factions pursuing their agendas in this adventure:

The aliens: obviously there are aliens here—in fact, there are a lot of them. We’ll talk about the aliens in tip #4 below.

The military: There’s a huge military presence near the colony in the form of Fort Nebraska. Although the adventure notes that it’s down to a “skeleton crew” of troops, that’s still about 200 personnel—a significant force. The commander in charge (who gives off real “Colonel Kurtz” vibes) is intent on evacuating with secret illegal alien research and wiping out all evidence of it on the way out. The military base is a huge “dungeon” filled with complications like a restrictive AI, a quirky android, and an unstable nuclear reactor; it could be the site of an entire adventure all by itself. Its space elevator is the “escape route” that DoW really wants the PCs to use to get off-planet at the end of the adventure.

The corporations: Mallory Eckford is a Weyland-Yutani corporate agent also looking for the AWOL marines; she has dispatched a team of hunters to find the missing soldiers before the PCs and/or the army do. She serves as a sort of wildcard in DoW and could be an alternating enemy and ally to the PCs.

The AWOL marines: four marines who have escaped from Fort Nebraska—some of whom have been infected/implanted by different strains of alien—are laying low around town, looking to escape and possibly blow the whistle on the alien research.

The UPP: The Union of Progressive Peoples (space communists) is planning a full-scale military invasion of the colony to seize the alien research in Fort Nebraska. This invasion occurs about halfway through the adventure as written.

Desperate civilians: the remaining population of the colony is in a panic to escape before the UPP invasion. Some are crowding at the local starport to find a way off the planet.

UPP sleeper agents: the local population has been infiltrated by UPP agitators who are spreading unrest and laying the groundwork for the coming UPP invasion.

Unidentified bombers: partway through DoW, an unidentified spacecraft appears and blankets the entire colony with the alien “goo” (as seen in Alien: Covenant). DoW deliberately does not tell the GM who this faction is or what they want, but it’s implied that they may be the bad guys from Heart of Darkness, the third published Alien RPG adventure.

That’s a lot of factions and agendas at play, and many of those agendas have been forming in the months before the PCs arrive on the scene. The PCs have no stakes in most of them. Think about the best Alien movies—how many competing factions do they feature? In most of the movies, you have two or three agendas that clash with and complicate each other. Having 6+ factions at work in one adventure is overkill.

Instead, consider choosing (say) three of those agendas and focusing on them, setting the others aside for now. The factions and agendas you choose can help you achieve a specific “feel.” For example, focusing on the UPP invaders and spies could add a Cold War “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” vibe. Focusing on the manhunt for the AWOL soldiers through a frozen, partly-abandoned colony could evoke some of the isolated frozen horror of The Thing. Focusing on the military and corporate shenanigans would highlight the dystopian hyper-capitalism of the setting.

My point is that choosing a few of these agendas and focusing heavily on them, rather than diluting all these themes by using them all at once, will give your DoW game a more coherent theme.

Tip #4: Use fewer aliens

Just like there are a few too many factions at play in DoW as written, there are too many aliens in it.

I know that probably sounds like heresy when talking about an Alien adventure. But DoW contains nearly every type of alien that has ever appeared in an Alien film, and a few that haven’t. Here’s the alien situation in the colony:

Regular xenomorphs: the PCs’ first encounter with an alien is likely with a single “regular” xenomorph, which they’ll hunt (and be hunted by) through the colony. This part of the adventure feels the most like Alien.

“Black goo” abominations: the PCs’ second encounter with aliens is likely to be with one or more of the “abominations” seen in Prometheus. These are humans that have been mutated into disturbing hybrids by exposure to the “black goo.” At some point the entire colony gets blanketed in this goo, turning the planet into a mutating hellscape.

An alien hive and queen: a whole hive of aliens, led by a queen, has taken root in the depths of Fort Nebraska. (The timeline of how and when this nest formed is a little fuzzy, like some other timeline details in DoW.) Assuming the PCs are evacuating via the space elevator, they’ll have to navigate a military complex overrun by an Aliens-style swarm of xenomorphs.

A “crusher” alien: in the alien hive is a special xenomorph called a “Charger,” a gigantic tank-like alien that would be an interesting “final boss,” except that there’s already a queen alien.

In addition to these, one or more PCs are highly likely to be infected by or impregnated with aliens, so you can count on at least one “Nostromo dinner table” scene.

I love all these aliens, but I think putting the entire Aliens bestiary into one adventure is too much. As with the factions in tip #3, I recommend choosing just a few alien types and centering the adventure around them.

The types of alien you choose will greatly affect the theme and even genre of the game you’re running. Choosing a few lone xenomorphs—setting the hive and Prometheus aliens to the side—will produce a tense, terrifying hunt atmosphere and would work well with mostly-civilian PCs.

Focusing on the hive as the main alien threat evokes the action of Aliens, especially if some of the PCs are heavily-armed marines.

Focusing on the Prometheus-style black goo aliens can emphasize body horror/transformation themes, and is a good way to keep the players on their toes (since the “life cycle” of these aliens is less well-defined and probably less familiar to the players).

Use the “charger” as a terrifying revelation for players who have seen all the movies and want something new.

When it comes to aliens in DoW, keep it simple! You can always complicate things later by throwing extras into the mix. As with the factions above, being intentional and spare with your alien threat lets you give your game a more consistent theme.

Bonus tip #5: Skip the opening briefing

This is a quick one, but: go ahead and skip the introductory “cutscene” where the PCs are briefed, then sent to Fort Nebraska to equip their search party. The briefing is a gigantic wall of text that you don’t want to read at your players. Instead, skip right to the action: start as the PCs step out of the cold and into the colony bar that will almost certainly be the first stop in their investigation. You can fill in briefing details as needed. If I had done this in my game, I would’ve cut out at least 30 minutes of meandering gametime that didn’t contribute much.

I hope you’ve found these tips helpful! If you’ve run DoW and have made alterations of your own to it, please share them below. DoW is a great adventure—it’s even better if you spend some time customizing it to deliver the exact experience your game table wants.

by

by

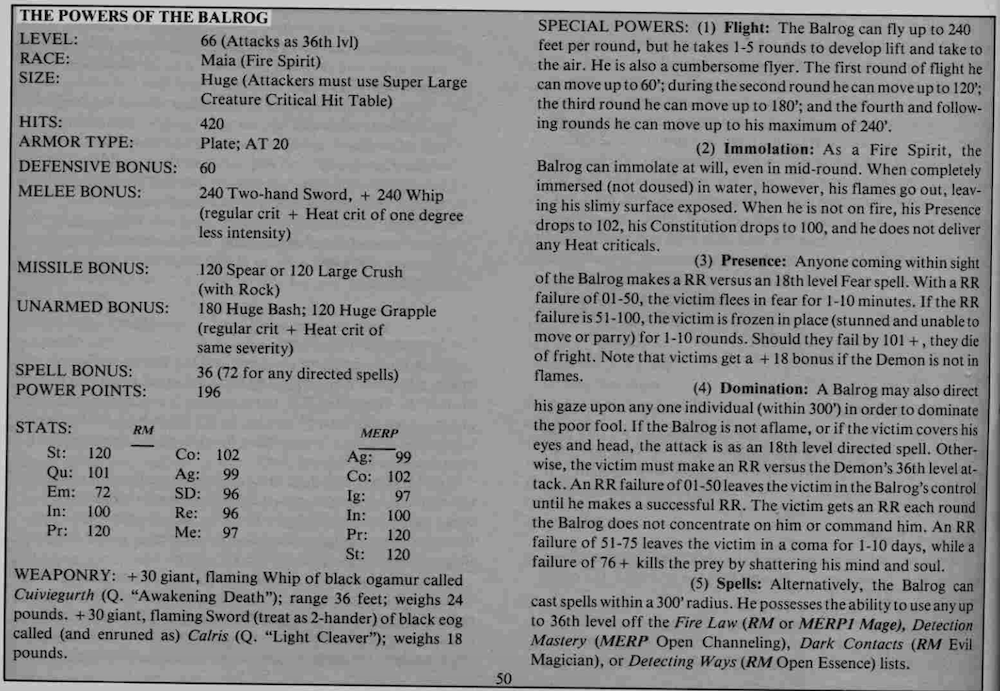

For as long as I can remember, I’ve done the same thing every time I’ve acquired a published adventure for Dungeons & Dragons or any other roleplaying game: I flip to the very end to see what the adventure’s Final Boss is.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve done the same thing every time I’ve acquired a published adventure for Dungeons & Dragons or any other roleplaying game: I flip to the very end to see what the adventure’s Final Boss is.