The inimitable Matt Wilson has posted some fascinating observations about how Diablo IV might benefit from the application of specific principles from the tabletop RPG world. He mentions, among other things, the game’s struggle to wed a largely linear gameplay experience with procedurally-generated content.

I’ve been playing Diablo games since the playable demo of the first Diablo game appeared (at the time, I was snobby enough to consider it a shallow ripoff of Nethack. You had to be there!). And here is a question I’ve never been able to answer:

Why does Diablo bother with randomizing content at all?

(I should note that I’m not sure whether the proper term to use here is “randomization,” “procedural generation,” or something else. I’ll use “randomization” and those of you who know better can just mentally translate that into the correct term.)

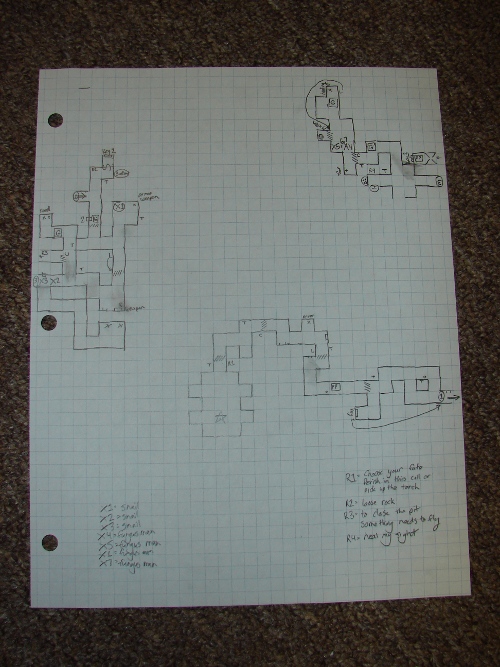

Randomized content has long been an integral feature of the Diablo series. Randomness in Diablo is used primarily to do (at least) three things:

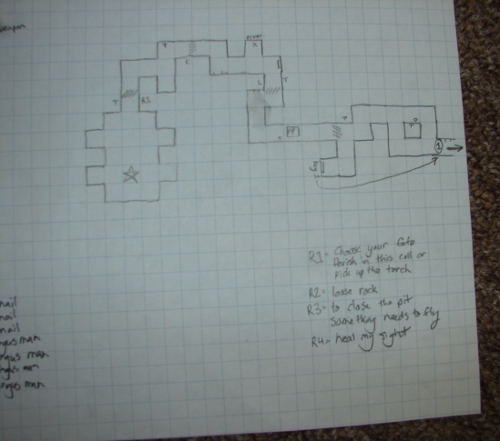

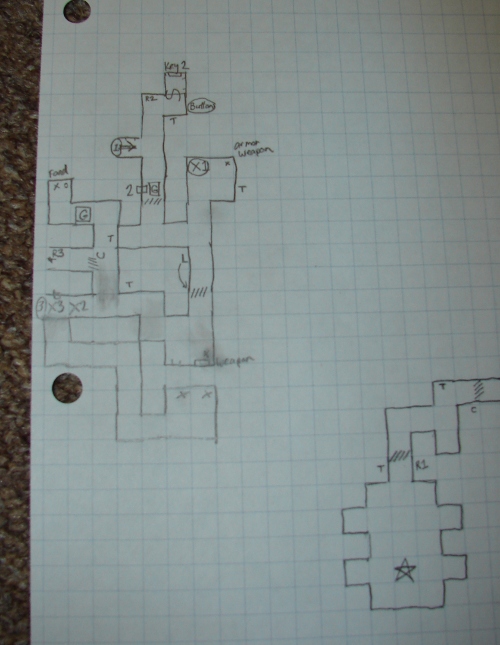

- Randomize the layout of the dungeons and areas you explore

- Randomize the architectural features and interactable objects in these areas

- Randomize the monsters you encounter as you explore these areas

(There is another major way that randomization is used—in the distribution of loot and equipment acquired from defeated enemies—but that feels less like procedurally-generated content and more like a carefully-tuned slot machine; while it’s not the type of randomness I’m talking about above, it’s perhaps the only random feature that delivers on its gameplay goals.)

The problem is that for all these presumably complex systems that randomly generate content and gameplay elements, the randomness has a negligible impact on the experience of playing the game.

The random layout of the dungeons has little effect on your game experience, as Matt notes: “Oh, they use a lot of art, turns, s-curves, etc. to try to disguise this from you, but every dungeon I saw was either a literal line or a line with one or two small offshoots.” Exactly. Slight tweaks to the ways that identical-looking hallways are connected do not make for a unique experience.

The random placement of architectural features and interactable objects similarly has little effect on your experience. Diablo dungeons are littered with randomly-placed objects that seem like they might turn the tide of a battle—a collapsible pillar, an explodable barrel, a drop-able chandelier—but they don’t actually do anything meaningful. They never do enough damage, or sufficiently affect the environment, to be worth interacting with instead of just standing there and mashing your attack buttons.

And likewise, the randomly-placed monsters almost never result in meaningfully different combat experiences. Diablo battles are fast and furious; they’re often so frantic that simply keeping track of what is happening is difficult. Different Diablo monsters might have different powers and weaknesses, but those differences rarely, if ever, prompt you to approach one fight differently from another. In almost all cases, your best strategy is to rush forward while firing your various attacks and spells as rapidly as you can.

What this all amounts to is that two different people playing through Diablo will never have meaningfully different stories about what they’ve experienced, despite all that randomness. None of the random elements are given enough scope to change your experience of the game, or for the narrow uniqueness of your playthrough experience to even register.

Contrast this to Diablo’s ancient roguelike ancestor NetHack; in NetHack, two players traveling through level 5 of the same dungeon would have massively different stories to tell about the experience. One player might have been pursued through a maze of twisty passages by a single relentless foe, using spells to survive until they could find the staircase to escape the level; while the other player might have had to dig his way through walls while avoiding hidden traps and fighting off hordes of tiny replicating enemies. Both players had an experience that was recognizably NetHack—they can relate to each other’s experience—but each player has a unique story about what they experienced (as well as a great incentive to replay dungeon level 5 to experience more fresh content). By contrast, two players who fight their way through the Halls of Agony in Diablo 3 would struggle to differentiate their experiences in any meaningful way; the dungeon layouts were different only in a very technical sense, and the fights were all a blur of button-mashing.

I should note that I don’t exactly mean to criticize Diablo for this. Diablo has its thing that it’s trying to do and it clearly works, since we’re still playing this series a quarter-century after its inception. It’s more that it simply baffles me: why build a complex system of interlocking randomness generators if, at every turn, you restrict the type of experience that randomness can create to a single flatly repetitive gameplay loop? If Diablo’s systems are meant to homogenize the gameplay experience and make it predictable, then the presence of all that randomness feels like a vestigial limb left over from a very different, 25-year-old vision of what Diablo might have been.