The hall closet in our apartment is, much to my wife’s dismay, stacked high with boardgames I’ve acquired throughout my sordid life as a gamer. Both of the adults in the family have degrees in archaeology, so perhaps it makes sense to view the tall stack of games in the closet as a sort of stratigraphy of my gaming life: the uppermost strata contain such recent artifacts as Arkham Horror and a few of the latest Axis and Allies releases; moving down the stack and back through time, one comes across Civilization, Gulf Strike, and Squad Leader; and buried in the bottommost layers are relics from my junior high and high school gaming days: B-17: Queen of the Skies, Battletroops, and other classics of yesteryear.

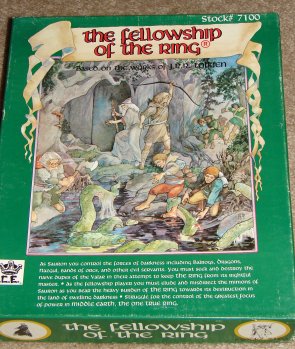

Today I want to reminisce about one of the games from the very earliest strata of that gaming pile–a curious and nearly-forgotten boardgame with which I was obsessed throughout junior high, and which eventually served as an entrypoint for me to the world of roleplaying games. The game is The Fellowship of the Ring, published in 1983 by Iron Crown Enterprises, and–like some of the Iron Crown RPGs I would later play–I loved it, although I didn’t always completely understand it.

Today I want to reminisce about one of the games from the very earliest strata of that gaming pile–a curious and nearly-forgotten boardgame with which I was obsessed throughout junior high, and which eventually served as an entrypoint for me to the world of roleplaying games. The game is The Fellowship of the Ring, published in 1983 by Iron Crown Enterprises, and–like some of the Iron Crown RPGs I would later play–I loved it, although I didn’t always completely understand it.

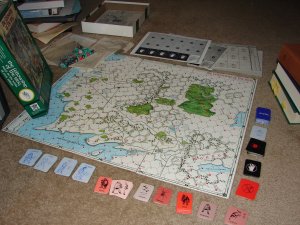

Fellowship is a two-player strategy boardgame that aims to simulate the events of the first half of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Physically, the game consists of a gorgeous hex-map of Middle-Earth (on solid cardboard, in six pieces that fit together), a whole bunch of colored dice (used as playing pieces rather than rolled, interestingly), a few small informational chits, and a huge number of cards (on rather thin cardstock; you have to punch them out before play) representing about every character and creature ever referenced by Tolkien. The production values are fairly impressive overall. (The map, like most of ICE’s Tolkien mapwork, is really nice; and I believe some of the character artwork cropped up in later MERP RPG books.)

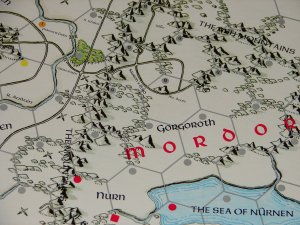

The basic gameplay consists of the Fellowhip (good) player trying to move the Ring as close to Mordor as possible, while avoiding evil agents and keeping the Enemy player in the dark as to the Ring’s actual whereabouts. The Sauron (evil) player uses his agents (Nazgul, monsters, and a slew of orcs, assassins, etc.) to locate and then take the Ring for himself. The game ends when the turn limit is reached, or when the Fellowship player declares the dissolution of the Fellowship, at which point a victor is determined by checking how close (and how quickly) the Fellowship player got to Mordor.

The basic gameplay consists of the Fellowhip (good) player trying to move the Ring as close to Mordor as possible, while avoiding evil agents and keeping the Enemy player in the dark as to the Ring’s actual whereabouts. The Sauron (evil) player uses his agents (Nazgul, monsters, and a slew of orcs, assassins, etc.) to locate and then take the Ring for himself. The game ends when the turn limit is reached, or when the Fellowship player declares the dissolution of the Fellowship, at which point a victor is determined by checking how close (and how quickly) the Fellowship player got to Mordor.

It’s a complicated game–and it seemed doubly complicated to me, given that Monopoly was the most complex game I was playing at the time I learned about Fellowship. Each of the dozens of characters and creatures in Fellowship has its own card with roleplaying-style stats (fighting power, defensive power, health points, etc.), and each player can have a fairly large number of units moving independently across the map during a typical turn. The Fellowship player can split his forces into numerous groups to keep the Enemy player from knowing for sure which one has the Ring; and he can also create “rumors”–fake groups that look like real ones to the Enemy player–to further deceive his opponent. The Enemy player, in turn, can send special agents like the Nazgul in pursuit of the Fellowship player’s various groups, and can flag one or more areas of the map each turn as the target of a thorough search, increasing the odds that any Fellowship groups in the area will be exposed and attacked.

If a Fellowship group is exposed by an Enemy search, it is attacked, either by specific Enemy creatures in the area or by randomly-drawn monsters depending on the terrain (orcs, trolls, spiders, etc.). A very RPG-style combat then ensues, with each player laying out his battle line (not unlike a Magic: the Gathering duel, actually) and attacking targets on the other side. Characters can be wounded, poisoned, or killed. The Fellowship player can usually deal rather easily with generic orcs and monsters, but if the Enemy player can keep dragging the Fellowship’s finite number of characters into combat with his limitless pool of monsters, he can wear down the Fellowship characters and eventually determine who has the Ring.

Overall, it’s a very clever game, and gameplay can be quite strategic and intricate. The Fellowship player is playing an elaborate bluffing game, trying to goad the Enemy into focusing on groups that aren’t carrying the Ring. He could send the Ringbearer’s group straight toward Rivendell and down towards Mordor, as in the books; that route lets him meet up with a lot of the trilogy’s most powerful good characters, but is also the route the Enemy will be watching the closest. Perhaps he should send a few “fake” groups towards along the direct route to Mordor, while the real Ringbearer takes a circuitous route southwest along the coast? Or maybe sneak the Ring across the mountainous northern edge of Middle-Earth, steering well clear of the more obvious routes? If the Fellowship player is smart, he’ll have groups heading in every possible direction, forcing the Enemy player to make hard choices about where to concentrate his searches.

Overall, it’s a very clever game, and gameplay can be quite strategic and intricate. The Fellowship player is playing an elaborate bluffing game, trying to goad the Enemy into focusing on groups that aren’t carrying the Ring. He could send the Ringbearer’s group straight toward Rivendell and down towards Mordor, as in the books; that route lets him meet up with a lot of the trilogy’s most powerful good characters, but is also the route the Enemy will be watching the closest. Perhaps he should send a few “fake” groups towards along the direct route to Mordor, while the real Ringbearer takes a circuitous route southwest along the coast? Or maybe sneak the Ring across the mountainous northern edge of Middle-Earth, steering well clear of the more obvious routes? If the Fellowship player is smart, he’ll have groups heading in every possible direction, forcing the Enemy player to make hard choices about where to concentrate his searches.

The Enemy player, on the other hand, has a huge advantage in terms of manpower, and has some truly scary monsters (the Balrog, dragons, the Watcher in the Water, etc.) he can use to guard important chokepoints on the map. He’ll win eventually if he can bog the Fellowship player down with repeated combats, and once he correctly guesses where the Ring is, he can focus a lot of nastiness on the Ringbearer’s group. His main disadvantages are that he can’t focus on all of the Fellowship groups at once, and must waste precious time exposing and eliminating the “fake” groups. And even when he manages to expose a Fellowship group, he can’t always control which of his forces are on the scene to attack.

Unfortunately, while the gameplay can be fairly deep and rewarding, the game rules are quite complicated–more complicated, I think, than they really need to be. The hit points of individual characters must be carefully tracked. Weather must be checked each turn. The mode of transit (horse, on foot, flying, etc.) must be determined for each group–and there can be a lot of groups on the board at one time. Some of the rules are just plain confusing, and I had to houserule more than one perplexing situation that cropped up during gameplay. Combat plays out much like it does in the Middle Earth Roleplaying Game, which is fun if you’re a veteran RPGer, but not so much if you are looking for a fast and exciting battle. It’s clear that the game was designed by people who played a lot of RPGs, and that doesn’t always translate into a fluid or fast-paced boardgame experience. (As it happened, Fellowship was what indirectly brought me into the roleplaying hobby. One of the first RPG products I bought, MERP: Riders of Rohan, I purchased because I mistakenly thought it was an add-on for the Fellowship boardgame.)

One final drawback: the game’s end-point, the dissolution of the Fellowship, feels a bit anti-climactic. Unfortunately, the game doesn’t have a good way of incorporating armies or epic battles (high points throughout Tolkien’s trilogy) into gameplay, and a Tolkien game without Helm’s Deep, Minas Tirith, and other epic battles feels like it’s missing something. Granted, the game sets out only to simulate the first book in The Lord of the Rings, but it feels like it could’ve done a bit more.

One final drawback: the game’s end-point, the dissolution of the Fellowship, feels a bit anti-climactic. Unfortunately, the game doesn’t have a good way of incorporating armies or epic battles (high points throughout Tolkien’s trilogy) into gameplay, and a Tolkien game without Helm’s Deep, Minas Tirith, and other epic battles feels like it’s missing something. Granted, the game sets out only to simulate the first book in The Lord of the Rings, but it feels like it could’ve done a bit more.

All in all, I would say that the game’s downsides are largely offset by its good points. The most appealing feature of the game is that you can try out alternate routes for the Fellowship to take to Mordor–and with all the monsters, encounters, and interesting characters that can come into play, the game at its best feels like you’re writing your own version of The Lord of the Rings. That’s fun, even if it is a gameplay idea that would be better served by a simpler set of rules. Despite its flaws, this is a truly unique boardgame, existing somewhere in the nebulous realm between roleplaying games and wargames. With the current state of the Tolkien license, I doubt this game will ever again see the light of day–but should you happen across a used copy somewhere, it’s certainly worth a look. It’s been gathering dust for years in my closet, but I look forward to breaking it out some rainy afternoon with a group of fellow Tolkien fans and rewriting the story of The Fellowship of the Ring.

A great article on a game with which I too was obsessed in junior high school. It’s really a shame that this game was never that popular, because its strengths, as you say, are considerable.

The complexity of the combat never really bothered me; indeed, as an RPGer, I thought that the wide range of characters with different stats was a really enjoyable element. I do think that the rules are not as air-tight as they could have been. There are always a few confusing moments in any given game where you have to interpret the rules. (It would have benefitted by a second edition.)

The only other thing that really bothered me was the generic Fellowship characters: why are they called “decoys”? The term is too easily confused with “rumors” , and it seems like laziness not to come up with some names.

Still, as you say, a great game, and well worth picking up if you can find it. I’m going to be playing it with a buddy next week and I can hardly wait.

Hey, great to hear from another person who remembers this game!

I do agree that a second edition might’ve been a good idea, had the game sold well enough to justify one. But definitely a good game despite its quirks.

I hope you’ll stop back on how your game goes next week. I’ve not played this game in a long time, and would love to hear an actual play report.

I have this game I want to sell it. It has been opened but never played!!