The story: “Umney’s Last Case,” collected in Nightmares and Dreamscapes. First published in 1993. Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A hard-bitten Chandler-esque gumshoe is plagued by the sense that something is “off” as he goes through a typical day on the job. In time, he learns that he is a character in a series of hard-boiled detective novels—and that the author plans to destroy his protagonist and take his place in this fantasy version of 1930s southern California.

My thoughts: As I’ve noted before, Stephen King has an unabashed love of hard-boiled detective fiction. “Umney’s Last Case” is both a pastiche of Raymond Chandler and a playful bit of meta-commentary on the art of writing.

My thoughts: As I’ve noted before, Stephen King has an unabashed love of hard-boiled detective fiction. “Umney’s Last Case” is both a pastiche of Raymond Chandler and a playful bit of meta-commentary on the art of writing.

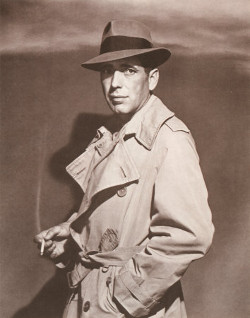

Let’s look at the pastiche element first. My knowledge of the hardboiled genre is limited, but I know enough to recognize that King here incorporates every cliché (of both setting and language) that the genre has to offer. Clyde Umney is a smart-mouthed, sharp-eyed P.I. who conceals beneath his gruff exterior a good heart. His is a comfortable world, both for him and for the reader: it’s full of familiar stereotyped characters (femme fatales, helpful street urchins, leggy secretaries, sinister mob bosses) who act and talk the way we expect, all in a slightly fuzzy, nostalgic version of Los Angeles.

But the story begins a shift into Stephen King territory when Umney’s life begins to fall apart: people he relies on leave (often expressing a strange contempt for Umney as they do so), his favorite diner closes, and his landlord is re-painting his dingy office building with bright, cheerful colors. It is not long before a “client” arrives to break the news: Umney is a fictional character, the protagonist of a popular detective series written in the 1990s. The “client” is the author, who (driven by personal grief) is seeking to escape into his own fantasies. Through some unexplained mechanism or act of willpower, he switches places with Umney, settling into Umney’s place and booting Umney into the real world. As the story closes, Umney is starting to get a grip on life in the modern world, which he hates. And he’s learning to write detective fiction, with payback on his mind.

As King is wont to do, he mixes lighthearted and serious elements, to mostly good effect. While clearly enjoying the detective genre, he has fun poking its conventions—for example, pointing out the blurry timeline (the genre is set in an eternal late-1930s). But when the story gets weird, it also takes a turn for the serious and even unsettling; we learn about horrible tragedy in the author’s life (death of his wife and child, debilitating illness) that has driven him to take refuge in his own fantasy world. There are numerous references to AIDS (the author’s child died after an infected blood transfusion) that highlight the contrast between the allegedly gritty but actually… cozy world of detective fiction, and the ugly, unfair, disease-ridden world of the present.

Beneath the genre emulation, King is asking some interesting questions about the art of writing. What is the relationship between an author and the characters he creates? Is there a sense that they take on a life of their own independent of the author’s plans? These questions have a certain over-earnest “Creative Writing 101” feel to them (and form the basis of his 1989 novel The Dark Half, which also features a writer of pulp fiction whose creations acquire a life of their own), but at the same time it’s fun to see them given literal expression in a story. King writes about writers a lot (eye-rollingly often, really), but between the fun pastiche, the Twilight Zone twist, and the musings about the nature of fiction writing, he makes this story work.

Next up: “One for the Road,” in Night Shift (yes, my wife located my lost copy of Night Shift).

The contrast between the supposedly gritty and the actually awful real world is interesting. I actually feel like reading this one. I wonder to what extent writers create the world they wish they could live in, though in Stephen King’s case that is a little worrisome. I think the main appeal is that the writer is in control, unlike in the real world, although in fact he isn’t entirely. Characters do veer out of control. And for readers the experience is safe, no matter how horrifying the content, because you know it isn’t real and you can stop reading any time. Perhaps that is the safety SK is trying to shake the reader out of, as you noted in previous posts. Anyway you are welcome for the return of night shift hehe.