A new post over at the Empires of Steel developer’s diary offers some interesting thoughts about incorporating religion into strategy games.

Category Archives: Computer Games

World of Xenophobia

Another odd but somehow entertaining piece about the problem of “Chinese farmers” in World of Warcraft.

Articles about “gold farming” and other bizarre MMORPG issues have been popping up frequently lately. The latest iteration is that some legitimate Chinese Warcraft players are being shunned by suspicious Western players, who assume that the Chinese players are gold farmers out to join up with an adventuring party, then snatch the best treasure and run at the first opportunity.

Having played the game semi-regularly for a few months now, I can’t say for sure that I’ve spotted any of these infamous gold farmers (although reading all the recent stories about them, you’d get the impression that nobody but gold farmers plays these games). I have run across a few people behaving rather suspiciously, but obviously it’s hard to tell from their in-game avatar if somebody is a foreign sweatshop worker or just a “legit” player with exceedingly poor communication skills and an alarmingly intense obsession with acquiring treasure. I guess I just like to give people the benefit of the doubt.

Only on the internet, eh?

Recycling games

Brace yourself, my friends, for a rant.

Saw an interesting piece this week at The Escapist about the importance of used-game sales in keeping computer/video game shops like EBGames and Gamestop alive. Here’s a rather eye-opening factoid:

GameStop executives describe this as a “margin growth” business – because they make a much higher profit margin on the sale of every used game than they do on the comparable sale of a new game. And in the highly competitive retail trade, margins matter. How much?

“Used games are keeping the entire ship afloat,” a vice-president of marketing for Electronics Boutique tells me. “EB and GameStop make basically no money from new product.”

Huh. I always failed to keep my lemonade stand running, but that doesn’t strike me as a stellar business model. And then there’s stuff like this:

Throughout most of the entertainment and media industry, when publishers want to make sure first-run entertainment sells in droves to the public, they charge what’s called “sellthrough prices” – and for virtually every form of media, including books, movies and music, that price is between $15 and $25. You can get the brand-new Feast for Crows hardcover for $16.80, the Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith DVD for $17.98, and Madonna’s Confessions on a Dance Floor for $18.98.

But you have to pay $49.99 for Perfect Dark Zero, or any other new release videogame. In comparison to its closest substitutes from other industries, videogaming isn’t priced to sell through.

And yet, selling through is the one thing a videogame must do. Videogames suffer from the shortest shelf life of any media.

My knowledge of large-scale economics is limited to what I learned in my high-school civics class, but it seems to me (and it’s seemed clear for a while now, actually) that there is a serious shakeup coming for the computer/video game industry. Full-priced sequels and retreads are released within a year of the original titles. Prices of new games are ludicrously high, enough so that this sad old game addict purchased only a handful of new titles in all of 2005 and will likely purchase even fewer in 2006. Even with $50 price stickers, margins are apparently so low that your local Gamestop has to hawk used games to squeak by. Where games were once programmed by nerds in their basements with too much spare time and a cool idea, they’re now cranked out by gigantic corporate teams with Hollywood-scale budgets. The latest round of consoles cost Joe Gamer a small fortune to actually purchase (and the games are sold separately!) but don’t, to my eyes at least, offer anything remotely resembling gameplay that is more fun than what I used to play on my NES.

People have been ranting about this for a while–Greg Costikyan railed rather gloriously about this last year–and you’re always hearing that direct-download game distribution (like Steam) is going to break down the current whacked-out game creation/distribution system, and every year people predict that the game industry is on the brink of another 1983-esque crash… but the months roll on, and the sequels are churned out, and the games still cost $50 (edging towards $60 now!), and old-timers like myself continue to gaze through rose-tinted nostalgia at the Commodore 64 gathering dust in the back corner of the closet.

Can’t say I have a point here, but it felt good to rant a bit. Now to go drown my gaming sorrows in the blood of my (online) enemies.

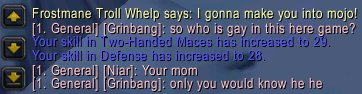

Welcome to the world of Warcraft

It was with some trepidation that I took my first uncertain steps into the wide wide World of Warcraft. An entire online world, waiting to be explored–quests to undertake, magical artifacts to discover, exotic locales to visit.

Questions gripped me as I logged in, created my character, and ventured out into the icy mountain wastes of Dun Morogh, south of the bustling dwarven city of Ironforge. Around me, a jaw-dropping diversity of interesting characters darted to and fro–dedicated players going about their adventurous business.

How would I adjust to the intense online interaction required by such an ambitious gameworld? Could my dwarf paladin, through hours of hard work, sacrifice, and valiant struggles against the forces of the Horde, achieve the respect and even the admiration of this community of online Warcraft veterans?

Wait–there’s a group of gnomes over there. Maybe they can answer a few questions for an inexperienced newbie player. What’s that, you say?

…oh.

I thought this place seemed familiar. Beneath the gorgeous graphical game interface, it’s the same ol’ internet I know and love.

This, I think I can handle.

On Starcraft and strategy

Brit has a good post up about a tricky design decision that goes into computer strategy games: the question of attack concentration. Pardon the lengthy quote, but here’s the section that particularly caught my attention:

If grouping units together increases their power, it means there is an incentive to group units together and a disincentive to split units apart. This fact affects gameplay in a major way. In games where there is a strong incentive for grouping, the progression of the game is rather predictable: expand until you encounter the enemy, maybe engage in a few skirmishes to capture objectives that the enemy hasn’t defended well (because he just arrived), build-up a large military, engage in one large battle which effectively determines the winner (the game may not end there, but the battle effectively determines the eventual winner), and then play out the foregone conclusion. The predictability of it is somewhat boring, and I get a little bored of the “military build-up” phase. I’ve seen a lot of games of Starcraft and Warcraft where this happens.

Brit here is pointing out something that any veteran Starcraft player (or any player of similar strategy games) has undoubtedly noticed: games between reasonably skilled players tend to follow the same basic pattern. Because of the way the game’s combat and other systems work, most games feature a relatively quiet, and often quite lengthy, period of military build-up followed by a massive, apocalyptic battle in which each side throws every conceivable unit into the fray. This massive battle either “breaks” one of the opponents, or (quite often) it ends with both sides’ armies effectively destroyed, prompting a second period of military build-up during which each side races to restore its fighting power before the enemy does. That’s a bit of an oversimplification, but it’s how games usually go.

This isn’t likely to interest most of you, but this got me thinking about the way that my Starcraft games against humans play out. Here’s what a typical game for me looks like:

- Phase 1: Establishing a presence (5 minutes): Each side scrambles to get a functional base. A few defensive structures and units are built, usually just enough to safeguard the fledgling base from a sneaky early-game rush attack from the enemy.

- Phase 2: Early build-up and expansion (5-10 minutes): Both players start building more advanced structures and begin to assemble an army. Scouts are dispatched around the map to hunt for mineral deposits. A few basic “recon” battles may occur as each side tries to get a glimpse of the other side’s army composition and general location.

- Phase 3: Skirmishes and expansion (15 minutes): Both sides make moves to claim any mineral deposits that haven’t yet been secured. Lots of skirmishing between medium-sized forces can happen, as both sides try to win “quick and easy victories” over enemy expansion bases that aren’t yet well-defended.

Almost invariably, during this phase, the “pivot point” of the map becomes clear: the strategic location over which almost all future battles will be fought. Often this is a rich mineral deposit located in the center of the map, which promises to provide a decisive strategic edge to whoever can claim final control over it. - Phase 4: Clash of the titans (10 minutes): Enough time has passed now that both sides have built up substantial armies, probably including one or two advanced unit types. Typically, a strategic stand-off settles in while each side carefully (but hastily) prepares for a huge offensive.

Somebody (usually the person who hasn’t been able to claim the pivot point, and thus feels pressure to reverse the strategic situation before it’s too late) pulls the trigger and launches a massive attack on the pivot point. The other player pulls in all forces to the defense and the battle is joined. Clouds of Terran battlecruisers and siege tanks, Protoss scouts and carriers, and Zerg hydralisks and guardians pour across the map.

This phase typically ends when both sides annihilate each other’s forces. Usually, somebody emerges from the uber-battle in better shape than the other player, but rarely with enough surviving force to go the final mile and win the game. - Phase 5: Frantic rebuilding (5-10 minutes): Both players retreat any survivors and immediately set to rebuilding their bases and armies as fast as possible. At this point, whoever can get even a medium-sized force onto the battlefield first usually has a big advantage.

Both sides often try “probing” attacks against the enemy’s main base, bypassing the pivot point, in the hopes that a decisive (even if under-strength) attack on a distracted enemy’s weak point will win the game quickly. (This usually doesn’t work.) - Phase 6: Armageddon (10 minutes): Somebody decides that their army is sufficiently rebuilt and launches a major attack. The other player responds by pulling in all available units to stop it. Because mineral supplies are running low, this fight usually decides the game. Often both sides annihilate each other again, but afterwards one side finds that it no longer has the economic ability to replace its losses. Although this player may have plenty of static defenses left on the field, it’s clearly just a matter of time before the other player slowly rebuilds and creeps inexorably across the map.

At this point, somebody usually surrenders rather than watch the enemy roll across the map uncontested.

Of course, the fun part of the game often comes in deliberately disrupting this schedule to throw off an enemy who’s expecting the game to play out in about this fashion. So many years after the game’s release, you’d think that it’s not possible to be surprised by enemy tactics and strategies… but almost every time I play, my opponent pulls off something new and interesting (and alarming).

That said, I’ve got a Starcraft game date set for later this week, and I wouldn’t want to reveal all of my strategies. Thanks, Brit, for giving me an excuse to muse on one of my all-time favorite games!

Where there’s a buck to be made

Massively-multiplayer sweatshops. I’m not sure exactly whether this is funny, disturbing, or just downright bizarre.

Into the mouth of (massively multiplayer) madness

Earlier this month, my resistance finally broke down and I ventured into the world of online RPGs. My poison of choice is Guild Wars, which lured me in with its lack of monthly fees.

So far it has been a great deal of fun. It’s easy to play, and lets you jump right into the action (going on quests, killing monsters) without having to worry much about leveling up, bartering for trade goods with 12-year-olds, conversing with creepy 48-year-old males playing buxom sorceress characters, or spending countless hours increasing your Underwater Basket-Weaving skill.

Will this become an addiction? Will my real-life personality slowly merge with that of Thagar Bloodaxe, mighty hewer of orcs? Will I end up Ebaying my wedding ring in exchange for in-game money with which to purchase stylishly-fashioned armor for my character? I’d like to hope not, but time will tell.

“Which way were we supposed to go, again?”: Information management in computer RPGs

I haven’t been doing too much computer gaming lately, but the one game I’ve been slowly working my through over the last few months is Morrowind, a fantasy RPG that had the misfortune of hitting store shelves at about the same time as Neverwinter Nights a few summers ago. Morrowind is, thus far, a very excellent game–its main feature is its extremely open-ended gameplay, with an almost bewildering amount of freedom given to the player.

While I recommend that you give Morrowind a try should you come across it, that’s not the main point of this little post. I’d like to think aloud for a moment about an oft-overlooked but important gameplay challenge that epic-scale RPGs like Morrowind face: helping the player keep track of all the information s/he comes across in the course of the game.

The world of Morrowind, and computer RPGs like it, is massive. The world map is sufficiently big that exploring it all could very easily take many dozens of hours of “real life” time; and the number of villages, cities, dungeons, and other Locations of Interest is enough to drive mad any but the most determined cartographer. When you consider that each location on the map can feature anywhere from 2 to 200 characters with whom to interact (“NPCs,” in RPG parlance), and each of those characters is ready to spout several pages’ worth of dialogue about the world of Morrowind and its secrets, the very thought of keeping track of all this information mentally is intimidating, to say the least. “What was the name of the town where I’m supposed to meet that contact, again?” the bewildered player soon finds himself asking. “What were the names of the local guild leaders? And did that guy say to turn north at the swamp, or south?”

Morrowind‘s sheer size makes it something of an extreme, but many RPGs suffer from being so big and populated that players can’t remember everything they’re told in the game. So how do RPGs go about trying to help players out in this regard?

In the Old Days, computer games didn’t really help you out at all, which meant that a pencil and notebook were the gamer’s most precious possessions–whether you were playing The Bard’s Tale or Ultima IV or Wasteland, chances are your computer desk was buried under sheets of notebook paper upon which crude maps, cryptic notes, answers to riddles, and passwords were scrawled. When, in their lair at the bottom of the Dungeon of Doom, the priests of the Mad God Tarjan ask you to state the password or die, you had just better hope that password is one of the many words scribbled on that piece of notebook paper!

These days, of course, games are both more complex and larger in scale than they were in the Glorious Days of Yore. They also, in some cases at least, attempt to store and manage your information for you. Morrowind does this fairly well, in my opinion, if not perfectly. It features an automatically-updating map of the game world, which is expanded and annotated as you acquire information and visit new locales. It’s a particularly helpful map in that it not only shows the main game world, but shows “local” maps with things like shops, temples, and other important buildings labeled so that you don’t have to remember which section of town houses the town hall.

Auto-maps like this are pretty common fare in RPGs these days, although most of them (including those in Morrowind) are missing a feature I think is almost ridiculously useful: the ability to mark and annotate the map yourself. Why does my map only show me the handful of locations deemed Important by the game designers? What if (as was recently the case for me in Morrowind) I want to stash all of my spare equipment and supplies in an abandoned building somewhere for later retrieval, but I don’t want to forget where that stash is located? It would be really nice if I could add labels and markers to the in-game map to note important locations like that, or to post “sticky note”-style reminders and notes to make sure I don’t forget important bits of information. I have seen this feature in only a small handful of RPGs (Baldur’s Gate II, I believe, was one of them), but I wish it were more common.

Keeping track of map locations is just one aspect of managing player information, however. The other major element is somehow recording all the important hints, secrets, names, directions, advice, and commands that you receive in conversation with the game’s NPCs. There are two extremes RPGs take in this regard: some, like Knights of the Old Republic, contain complete logs of every conversation you have in the course of the game, and let you browse through the conversation logs if you need to track down a specific piece of information. Other games, like Morrowind and most of the Black Isle RPGs, contain an automatically-updated “journal” that records basic summaries of plot-important conversations.

There are problems with each extreme. The first method–recording complete logs of all conversations–is useful in that it puts the maximum amount of information at your disposal, but is incredibly unwieldy. Are you really going to dig through dozens of conversation logs in search of some isolated line of important dialogue? The other method–the automatic journal summary–is useful because it distills all of your conversations down to just the plot-important ones, but can quickly start feeling like a checklist of tasks, not a real diary of one’s experiences. I remember only one game that let you keep your own in-game journal (Baldur’s Gate II), and I must say, it added tremendously to my experience to be able to keep my own notes (both in-character and out-of-character) during the game.

I’d love to see these methods of tracking game information improved and expanded. The automatically-updating maps are already quite useful, although they would benefit from being editable by the player. The conversation-tracking and journalling can use some more substantial improvements, however. To that end, I’d love to see an RPG that includes some of these features:

- a simple, Google-style search engine I can use to search through conversation logs for keywords

- an in-game player journal (in addition to, or integrated with, any automatically-updated journal)–preferably a full-blown text editor, complete with basic text formatting options

- the ability to associate certain journal entries with specific points on the map, so that clicking on parts of the map would also highlight all journal entries (or conversation logs, or any other notes you’ve taken) that relate to that area

- a “sticky note” feature that would let you attach sticky notes to any part of the game interface

I’d love to see some of these features added to future RPGs. I’m sure that some of them will be (or already are) incorporated into games, but I have a feeling that the relative thanklessness of designing this aspect of a game will keep these sorts of tools very much on the back burner in most RPGs (are game reviewers more likely to praise a game’s mind-blowing graphics, or its map-annotation features?). Nevertheless, I think the careful application of some of these features would improve gameplay in subtle but important ways.

I have failed you for the last time

In looking back over the ol’ blog, I realize that I failed to deliver my promised discussion of scary computer games. That’s what happens when you violate Blogging Rule #37 (“Never Make Rash Promises About Future Posts”). Ah well–it’s a topic that interests me, so I wouldn’t be surprised if I discuss it at some point in the near future. But I’m not promising, mind you.

With apologies to C.S. Lewis

Dear Mr. Asmodeus,

As you know, I was recently contracted by the Higher Powers to conduct an independent audit of Hell’s operations and security in the aftermath of last week’s incident (hereafter “The Incident”). I refer to the events of last Monday, when a lone Space Marine gained entry to Hell and, in the course of just a few hours, inflicted a staggering amount of damage to Hellish property and personnel.

The Incident has effectively disrupted Hellish operations (not to mention its budget) for the indeterminate future. It takes time to re-spawn so many slaughtered demons, and in the meantime, temp workers must be hired to torture the souls of the damned. In addition to the costs of breeding and training an entirely new staff, we are now faced with the considerable challenge of finding a construction contractor willing to descend into the Stygian depths to repair the very extensive structural damage. We may even be forced to temporarily suspend the processing of newly-arrived souls due to these personnel losses.

Management tasked me with a straightforward job: review current Hellish security and operations and recommend action steps that will ensure that this sort of thing never happens again. Over the last week, I have interviewed survivors of The Incident and toured the nearly-demolished facilities in search of ways to avert future Incidents. I am pleased to present the following recommendations, which I feel will significantly decrease the chance that the legions of Hell will ever again be slaughtered by a lone Space Marine and his shotgun.

1) Better Master Plans. No offense is intended to you or your strategic planners, but it should be noted that this Incident–actually the third such Incident–occurred during your efforts to, and I quote, “bury the pitiful souls of humanity beneath a tidal wave of eternal darkness.” During all three of your invasion attempts, a Space Marine has sneaked into Hell and wreaked havoc. Future invasion plans should budget more money towards protecting the Hell-gates, perhaps by fencing them off or requiring I.D. checks at entrances.

2) Clutter Control. The severity of The Incident would have been greatly reduced had the Space Marine intruder not been able to find and use health packs, ammunition, and high-tech weaponry that were inexplicably scattered–unattended and unsecured–throughout the Abyssal caverns. There is absolutely no good reason to leave rocket launchers and chainguns (or ammunition for them) lying around on the ground where they can be picked up by any passing Space Marine. I recommend that you increase the janitorial budget, institute a stricter “clutter-free workplace” policy, and do everything possible to keep cutting-edge weaponry safely and legally secured and out of reach of intruders.

3) Better Combat Training for Personnel. Many casualties could have been avoided had the Hellish hordes received better training in basic combat tactics. It is important that Hellish staff be able to adjust their combat tactics in response to the Space Marine’s own actions. This is most important for your so-called “Boss” personnel, many of whom were tragically killed because they refused to deviate from their “patterns of attack” despite the fact that the Space Marine had clearly caught on to their tactics and was exploiting them. In one instance, two otherwise intelligent Hellknights were left hopelessly confused by the Space Marine’s strategy of ducking behind a pillar in the middle of the room. A demon with a more “can-do!” attitude would have investigated the pillar instead of standing still and being repeatedly struck by missiles until he died. I recommend longer and more in-depth combat training for all Hellish denizens.

4) No Toying Around. I know it is tempting to “play” with the Space Marine–gloating, issuing threats, and “toying” with him by letting him live just to see if he is able to overcome your fiendish traps and demonic guardians. However, after a certain point, I recommend that you stop toying with the Space Marine and simply kill him. For instance, instead of blowing up a bridge in front of the Space Marine and then gloating that he will never find a way across the chasm, why not just blow up the bridge while he’s walking across it? It’s less satisfying, but letting him live because you find his “pitiful” efforts “amusing” is just inviting the sort of disaster we experienced last week.

I think you will find that applying these recommendations to future operations will significantly decrease Hell’s vulnerability to lone Space Marines, and will improve morale amongst a demonic workforce that has suffered through not one, not two, but three Space Marine rampages in the space of only ten years. I hope you find my report helpful, and would be more than happy to assist you should you have any questions about it. I remain

your faithful servant,

Mephisto

Auditor from Hell