One of the first events I attended at Origins this summer was a small roundtable discussing the topic of ethics in gaming. How should one approach dark, evil, or morally ambiguous themes in a roleplaying game? Of the three forum participants, I recognized two as having written game material that would have, back in the Old Days of gaming, sent Jack Chick into an apoplectic frenzy; so naturally I was interested.

It was, indeed, an intriguing discussion that showed me a few new ways to think about the topic. While I’m not usually one to explore Dark and Mature Themes in my roleplaying games (no matter how hard I try, my Call of Cthulhu games usually end up as pulpy, tongue-in-cheek affairs), it is heartening to see that behind the surface-level shock value of, say, a game supplement about satanism, there is an author who is fully aware of the ethical territory into which he’s ventured, and who is determined to handle the topic responsibly. Of course, not all game authors approach gray moral issues with such care, but I have renewed respect for those who do.

One of the most interesting points brought up during the discussion, however, was that ethical issues can crop up even in types of games we don’t normally think of as dark or controversial. One of the presenters–Ken Hite, I believe–pointed out that players can run into moral quandaries even in a area of gaming like historical wargames–a genre I’d generally perceived as so clinical in its approach to its subject matter as to leave little room for shades of gray. Hite mentioned a wargaming friend who refused to play the side of the Confederacy in any wargame (presumably because of its support for slavery, although I don’t think Hite specified). For this player, no matter how historical, detached, or neutral the game’s approach, taking on the role of the Confederacy was a moral line he was unwilling to cross.

Normally I might not have given this point much consideration. I enjoy historical strategy and wargames, but I’ve rarely thought of them as having an ethical edge–I’ve never seen anyone object to playing the Germans in Axis and Alies, and wargames that deal more closely with ethically-blurry conflicts (such as wargames about the Arab-Israeli wars or the German-Russian front in World War II) are careful to focus purely on the clash of military forces, avoiding the atrocities and war crimes that sometimes accompanied them.

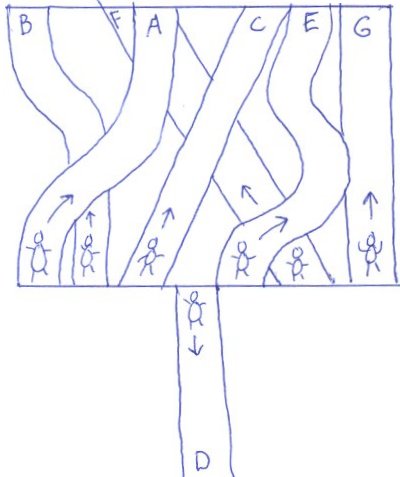

All that to say, I’m not accustomed to viewing the hobby of wargaming as an activity with serious ethical elements. But the very next day at Origins, I was surprised to find myself catching a glimpse of that moral line–in Advanced Squad Leader, of all things. The final game I played in the small Origins ASL tournament was a scenario called “Mila 18”–depicting a Jewish revolt in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943. One person controls the poorly-armed but determined Jewish fighters, while the other player controls the SS troops sent into the Ghetto to crush the revolt by killing and rebels and “mopping up” the Ghetto’s buildings.

Now, I suspect that the Mila 18 scenario is intended as a salute to the bravery of the Jewish fighters who rose up to fight the Nazis against overwhelming odds. (It certainly isn’t any sort of glorification of the SS.) But it felt vaguely uncomfortable to control the German troops–and not just generic “German troops,” but a specific historical SS unit–sweeping through the Ghetto carrying out a mission that was evil by any objective standard.

Why did it make me uncomfortable? Under ordinary circumstances, I have no moral qualms about simulating historical military actions on the board of a wargame, however brutal those battles were in real life; but the looming shadow of the Holocaust cast this scenario in an entirely different light. Although I played out the scenario to the end (the Germans lost), I didn’t like pushing those little SS markers around on the gameboard. Does a scenario like Mila 18 cheapen the memory of the real-life sacrifice and murder that took place there–and if so, why does it prompt moral discomfort when a scenario about, say, the Normandy invasion does not? Or is this scenario an important, maybe even critical, reminder that no matter how far we try to distance ourselves from the real horror of the wars we clinically simulate, there remains a serious ethical element to wargaming?

In the end, it’s a game and a hobby, and I probably won’t lose sleep over it. But I think it’s healthy to periodically stop and consider where our ethical boundaries lie, even for something like gaming. And I’m always up for a good game of Advanced Squad Leader, but next time I think I’ll stick to more uplifting parts of the war–like the Eastern Front, or the Pacific War, or… ah, never mind.

by

by