For as long as I can remember, I’ve done the same thing every time I’ve acquired a published adventure for Dungeons & Dragons or any other roleplaying game: I flip to the very end to see what the adventure’s Final Boss is.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve done the same thing every time I’ve acquired a published adventure for Dungeons & Dragons or any other roleplaying game: I flip to the very end to see what the adventure’s Final Boss is.

So you can imagine my joy when I first got my grubby teenage hands on the ultimate fantasy megadungeon and feverishly flipped to the end of the book to read up on the most famous dungeon boss of all. I’m talking about the Mines of Moria, and the famous Balrog that lurks in its depths.

That’s right: in 1984, Iron Crown Enterprises published Moria: The Dwarven City, a 72-page sourcebook detailing Moria for the Middle-Earth Role Playing game (MERP) and its sister game Rolemaster. And sure enough, there at the end are stats for the Balrog.

So could your plucky band of adventurers actually take out Durin’s Bane? Let’s find out!

Reducing Durin’s Bane to a bunch of numbers

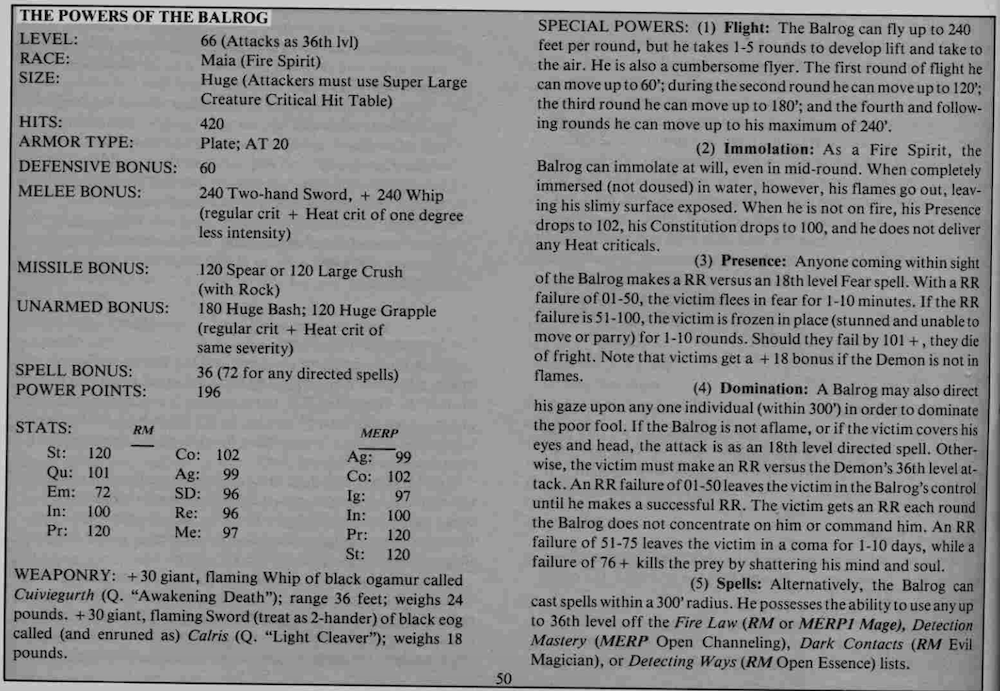

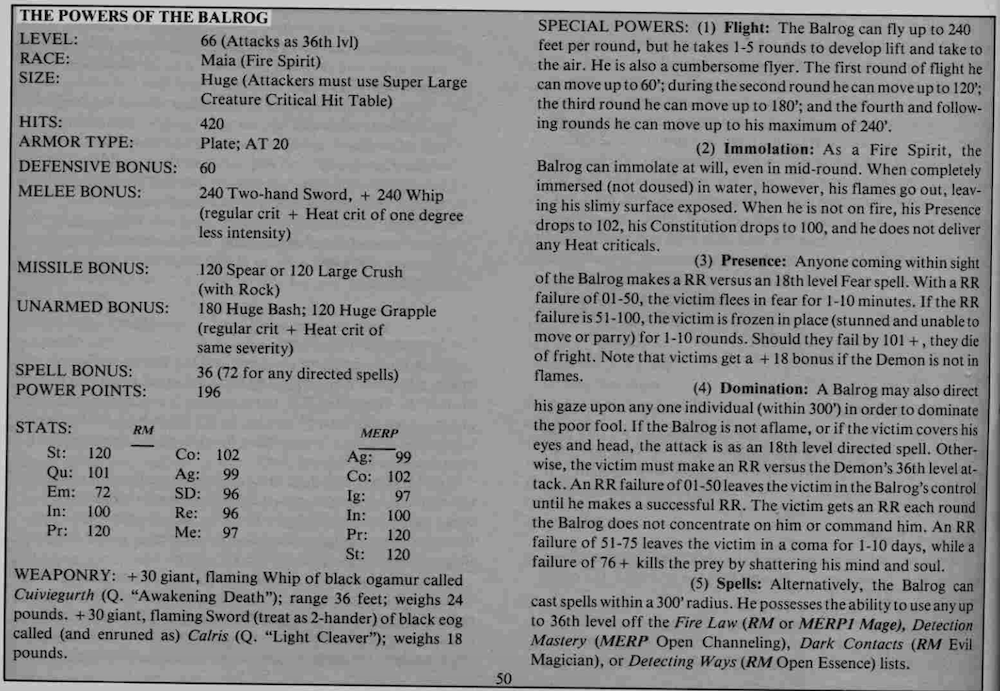

Here’s the Balrog’s game statistics and powers:

Egads, that’s a lot of gibberish. What does all that information mean?

Well, for starters, the Balrog is level 66. (Confusingly, the game rules handle it as level 36 for certain attack purposes, hence the number 36 in there.) The Balrog is much higher level than your characters are or ever will be. The longest-running MERP campaign I ran, way back in high school, stretched on for a couple years and when it ended, the PCs were in the level 15-20 range. I think it’s safe to say that unless you’re playing with the world’s most generous dungeon master, you’re never going to get a MERP character leveled up to match the Balrog’s power level.

A 1977 illustration of the Balrog by Greg and Tim Hildebrandt.

The rest of those numbers all boil down to this: the Balrog is extremely powerful in combat and very hard to kill. It’s got a huge amount of hit points and high defenses; combat skills so high that it’s virtually guaranteed to land a one-shot killing blow against anything it swings a weapon at; and the ability to mentally control enemies and/or freeze them with fear. It also has limited flight (the game designers have taken a stand in one of the internet’s oldest debates.)

Does it have weaknesses? Well… the Balrog is a bit of a one-trick pony; it’s an insane combat monster but has few powers that aren’t related to fire or killing. It knows lots of fire-related magic (fireballs and the like); but the other spells at its disposal have less utility in combat, and seem to be geared toward negating obvious player tricks (like an invisible character sneaking up on it…) or keeping track of its domain. When it comes to magic, an extremely powerful wizard (like Gandalf) would have some advantages… as long as they could keep away from the Balrog’s sword and whip.

The Balrog does have one single relatively low statistic. That’s right—just as you suspected, the Balrog lacks empathy. (Bad joke aside, Rolemaster’s “empathy” stat governs a character’s affinity for divine and healing magic. No surprise that’s not the Balrog’s strong suit.)

Most significantly, because it’s a being of fire, its strength and powers are significantly muted if the Balrog is completely submerged in water. A waterlogged Balrog will probably still pulverize you, but it won’t be able to set you on fire while doing so.

Is this faithful to Tolkien’s depiction of the Balrog?

As adaptations go, it’s not bad! From scattered references in various Tolkien texts, we know that Balrogs are pretty much just really tough, mean fiery guys (who can maybe fly). There’s not much depth to them beyond that, either here in the game or in Tolkien’s novel. As statted up here, the Balrog is certainly physically powerful and on fire, and its ability to terrify victims is in keeping with what we see in The Fellowship of the Ring. (It also fits the Tolkien theme of evil as the imposition of one’s will on somebody else.)

If anything, the designers may have even gone a little overboard with the Balrog’s physical power. But it’s hard to get an accurate read on exactly how deadly Tolkien bad guys are in a fight, because so many of them are “plot device” monsters (more on that below).

Is it killable?

The quick answer is “no.” In a straight-up fight with a party of typical player characters, it’s hard to see how the Balrog could lose. Any enemies that got within combat range without being dominated or frozen in fear would quickly get incinerated and/or annihilated.

But of course, the longer answer is… “maybe.” Every experienced dungeon master has watched in horror as players managed to take down a powerful monster by surrounding it and hammering it with spells and attacks; no dungeon master should assume that a lone enemy, even one this powerful, is invincible. The Moria sourcebook anticipates this by noting that the Balrog is accompanied by a host of trolls, demons, and orcs—all of them much less powerful than the Balrog, but easily able to bog down a team of adventurers while the Balrog picks them off.

But in the end, a group of high-level characters, while not a direct match for the Balrog, command significant powers and abilities; it’s very hard to predict the kind of advantages they could create for themselves by working in concert. You can bet they’ll be coming up with ridiculous schemes to drop the Balrog into a lake, or collapse a few hundred tons of cave ceiling down onto it, or something else. An indirect, story-driven approach that avoids physically battling the Balrog is the only way I could possibly imagine a band of adventurers taking down Durin’s Bane.

If it’s not killable, what’s it doing in the game?

Mostly I think this is just a fun exercise to “stat up” one of fantasy literature’s most famous boss monsters. Certainly, I enjoyed poring over these numbers as a teenage gamer, imagining what a Balrog showdown would look like. Be honest: you’d be disappointed if you picked up a roleplaying module about Moria and it didn’t have stats for the Balrog.

But how would you actually use the Balrog in a regular game? MERP is mostly interested in defining the Balrog by its tactical combat abilities, which are far beyond the typical adventuring party’s. But although the module doesn’t discuss it, the Balrog is really a “plot device” monster, like most evil overlords in fiction. Most of the evil bosses in Middle Earth seem nearly invincible in combat but can be defeated by a hero who works out their unique weaknesses and exploits them for narrative effect. Think of Smaug (weakness: that one missing scale), Shelob (weakness: Elvish magic, hobbit tenacity), Sauron (weakness: the Ring), the Witch-king of Angmar (weakness: women), etc. It could be very satisfying to watch the players work hard to uncover the Balrog’s one weakness and use it to banish or destroy the demon without getting into a big physical fight. Finding that weakness would be an epic quest in itself, which sounds perfect for a roleplaying game.

If you’re itching to see the Balrog’s +240 whip attack in action, though, there are a few possibilities. One could see the appeal of an extremely high-level “Balrog hunting” game, in which players control canonical movers and shakers like Gandalf, Saruman, Elrond, and Galadriel in a high-powered raid on Moria. Those characters are statted up in other MERP sourcebooks, and as a team would be a match for the Balrog.

And lastly, bold lower-level characters traveling through Moria might have a close brush with the Balrog without actually engaging it in combat. A group of extremely clever and lucky characters might try stealing treasure from its lair and making a mad dash for the exit before it notices or catches them, much as Bilbo Baggins did with Smaug.

But mostly, it’s just fun to stat up the Balrog.

by

by

For as long as I can remember, I’ve done the same thing every time I’ve acquired a published adventure for Dungeons & Dragons or any other roleplaying game: I flip to the very end to see what the adventure’s Final Boss is.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve done the same thing every time I’ve acquired a published adventure for Dungeons & Dragons or any other roleplaying game: I flip to the very end to see what the adventure’s Final Boss is.

The purpose of the Mini RPG Fest is to provide a place where the general public can try out different roleplaying games in a casual and friendly environment. Most games are only one hour long, so you can sample different games as you like.

The purpose of the Mini RPG Fest is to provide a place where the general public can try out different roleplaying games in a casual and friendly environment. Most games are only one hour long, so you can sample different games as you like.