The story: “Battleground,” collected in Night Shift. First published in 1972. Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: After murdering his latest target—a toy company executive—a hitman receives a package in the mail… from the victim’s mother. It’s full of little G.I. Joe toy soldiers, who come to life and wage an extended battle against the hitman in his high-rise apartment.

My thoughts: Short, simple, and fun, “Battleground” isn’t the sort of story that invites deep reflection or discussion. There’s just something wonderfully appealing about the thought of a troop of little green plastic soldiers running around performing cute little military maneuvers. But let me point out a few things.

My thoughts: Short, simple, and fun, “Battleground” isn’t the sort of story that invites deep reflection or discussion. There’s just something wonderfully appealing about the thought of a troop of little green plastic soldiers running around performing cute little military maneuvers. But let me point out a few things.

First, by an odd coincidence this is the second story featuring a hitman protagonist that I’ve read this month. I don’t think King does this especially often (King superfans, please correct me); but a hitman does have a few benefits as a protagonist in a horror story. For one, they’re usually armed and dangerous, so you can drop them into tight situations and expect that they’ll put up a good fight. For another, they’re by definition bad people—so while we might cheer them on as they face off against supernatural threats, we don’t mind when they inevitably die in the end. They deserve it.

Secondly, this story, short as it is, accomplishes something that many horror films and stories do not: it skips the usual extended sequence where the protagonist, confronted with evidence of the supernatural, spends a long time questioning his sanity and trying to explain away the situation rationally. When the reader/audience knows for certain that the supernatural element of the story is real, it’s tedious to wait for the protagonist(s) to finally catch up. In “Battlefront,” we get to jump right into the action because Renshaw, the hitman, always puts the practicalities of survival first: it might make no logical sense that he’s being attacked by toy soldiers, but he’ll ask the troubling questions after he’s taken care of the threat.

Unfortunately for Renshaw, he’s not going to survive this engagement. He puts up a good fight, taking down toy helicopters and dodging rocket attacks as he makes a fighting retreat into his apartment’s bathroom. After a humorous nod to World War 2 general Anthony McAuliffe’s famous “NUTS” letter, Renshaw comes up with a desperate plan to sneak around the outside of the high-rise and surprise-attack the toy soldiers with a homemade Molotov cocktail. Unfortunate for Renshaw, he underestimates the firepower at his enemy’s disposal; he is blasted to pieces when the soldiers detonate a toy nuke.

Although “living dolls” and other animated toys have a history of being utterly terrifying when deployed in horror stories and film, the animated soldiers here are not scary; I was cheering them on throughout and hoping they’d manage to take down Renshaw. It’s a funny story, and like “The Reaper’s Image” early this month, makes for a nice bit of filler to read in between more intense King short stories.

Next up: “Night Surf,” in Night Shift.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A handful of passengers on a red-eye flight across America wake up to find that the rest of the passengers—and the plane’s crew—have vanished into thin air. They manage to land the plane (one of the group is a pilot), only to find that the world is gray and dead—they have gone back in time, but it turns out the past is an empty shadow of the present. And strange creatures called the langoliers, who “tidy up” history by literally devouring the past, are headed their way.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A handful of passengers on a red-eye flight across America wake up to find that the rest of the passengers—and the plane’s crew—have vanished into thin air. They manage to land the plane (one of the group is a pilot), only to find that the world is gray and dead—they have gone back in time, but it turns out the past is an empty shadow of the present. And strange creatures called the langoliers, who “tidy up” history by literally devouring the past, are headed their way. My thoughts: Another vampire story! “One for the Road” is best read as an epilogue to the (excellent) vampire novel ‘Salem’s Lot; without that context, it loses much of its impact. Whether or not you read it in connection with that novel, however, this is a short, simple story that belongs to the “Want to hear about something spooky that happened to me?” around-the-campfire genre. It all builds to the vampire encounter in the final pages—a conclusion that is telegraphed from the story’s opening pages but is nonetheless creepy and tense when it unfolds.

My thoughts: Another vampire story! “One for the Road” is best read as an epilogue to the (excellent) vampire novel ‘Salem’s Lot; without that context, it loses much of its impact. Whether or not you read it in connection with that novel, however, this is a short, simple story that belongs to the “Want to hear about something spooky that happened to me?” around-the-campfire genre. It all builds to the vampire encounter in the final pages—a conclusion that is telegraphed from the story’s opening pages but is nonetheless creepy and tense when it unfolds. My thoughts: As I’ve

My thoughts: As I’ve  My thoughts: Stephen King writes good vampire stories. I sometimes think it’s a shame he doesn’t write more of them.

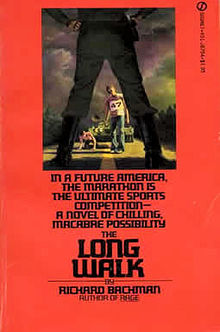

My thoughts: Stephen King writes good vampire stories. I sometimes think it’s a shame he doesn’t write more of them. My thoughts: Like Stephen King’s other early “Bachman” novels, The Long Walk is not a supernatural or traditional horror story.It is instead a precursor of the “teen dystopia” genre dominated today by the Hunger Games books. Set in an alternate-history modern America, The Long Walk follows the teenaged participants in a gruesome national pastime: a walking marathon that ends when only one walker is left standing.

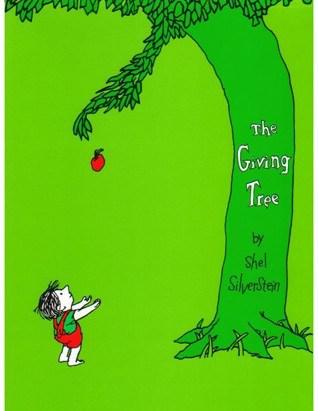

My thoughts: Like Stephen King’s other early “Bachman” novels, The Long Walk is not a supernatural or traditional horror story.It is instead a precursor of the “teen dystopia” genre dominated today by the Hunger Games books. Set in an alternate-history modern America, The Long Walk follows the teenaged participants in a gruesome national pastime: a walking marathon that ends when only one walker is left standing. At its heart, this is a story about the sacrifices a mother makes for the sake of her child. Martha, the protagonist, is a poor black woman married to an abusive thug during the Civil Rights era. Pregnant, confused and desperate, she seeks out the counsel of a

At its heart, this is a story about the sacrifices a mother makes for the sake of her child. Martha, the protagonist, is a poor black woman married to an abusive thug during the Civil Rights era. Pregnant, confused and desperate, she seeks out the counsel of a