I just watched The Black Hole with Michele. I haven’t watched it in probably twenty years, but it’s always held an extremely powerful nostalgic pull on my imagination. When I was a kid, I went through a period of obsession with this film—we’re talking a Black Hole lunchbox, a Maximillian model, a Black Hole storybook/record… the works.

I just watched The Black Hole with Michele. I haven’t watched it in probably twenty years, but it’s always held an extremely powerful nostalgic pull on my imagination. When I was a kid, I went through a period of obsession with this film—we’re talking a Black Hole lunchbox, a Maximillian model, a Black Hole storybook/record… the works.

I don’t know why it’s taken me so long to revisit this as an adult. It’s widely regarded as a mediocre film, and perhaps my subconscious has been trying to spare me the tragedy of seeing a piece of nostalgia exposed as just another overwrought B-movie.

But having re-watched it at last, I’m happy to say that, to my surprise and relief, I very much enjoyed it. For all its shortcomings, it works—the whole turns out to be much more than the sum of its parts.

While it’s fresh on my mind, here are a few of the elements that make The Black Hole shine, despite the failings that critics have, with just cause, pointed out.

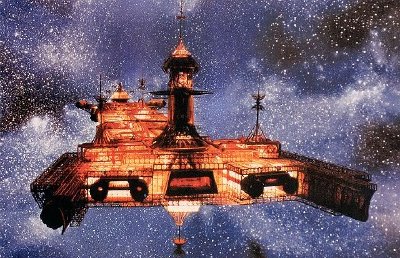

1. The ships and effects. Put simply, the spaceships, set design, and overall visual atmosphere are superb. The Palomino nails the Millenium Falcon aesthetic: a bit ugly and looking like it’s been around the block a few times, yet rugged and appealing. But of course the Cygnus, palace of the mad space scientist Dr. Reinhardt, is the star of the show; it’s one of the most unique and impressive-looking spaceship designs I’ve ever seen. Its strange latticework structure; its cathedral-like spires; the cavernous inside spaces that make life seem so tiny and out of place inside it. Other films have used spaceship design to suggest a cathedral-in-space (Event Horizon‘s Core, the recent Battlestar Galactica‘s Resurrection Ship; the Auriga of Alien: Resurrection), but none match the Cygnus, a drifting temple to its captain’s hubris.

The Black Hole will also make you pine for the days before real, actual, physical models were replaced by the CGI apocalypse. There’s a visceral, tactile appeal to the models here that more than compensates for the now-dated special effects.

2. Dr. Reinhardt is a wonderful villain. He’s a great mad scientist in the classic vein. Those fools told him that what he was doing was impossible, even insane! But he’ll show them. It’s probably a serious misstep that The Black Hole makes Reinhardt’s Ahab-style madness apparent from his very first appearance; it dulls the impact of our eventual discovery that he’s a totally crazy murdering megalomaniac. But hey, we knew that anyway, and it gives Maximilian Schell lots of opportunities to ham it up.

3. It’s weird and dark, with lots of unnerving details. The “robot” unmasking scene scarred me for life as a child, and it retains some of its shock value today even though it’s obviously a guy in makeup. The “robot” funeral leaves you wondering uncomfortably how much humanity might still lie buried away, despite one character’s insistence that the mental damage is irreversible. At one point, after the deeply creepy Maximillian has murdered Kate’s crewmate, Reinhardt leans close to her and begs her to protect him from Maximillian. Is he mocking her? Is he living in constant terror of Maximillian, who might really be running this horror show? Wonderfully, the movie never tells us.

3. It’s weird and dark, with lots of unnerving details. The “robot” unmasking scene scarred me for life as a child, and it retains some of its shock value today even though it’s obviously a guy in makeup. The “robot” funeral leaves you wondering uncomfortably how much humanity might still lie buried away, despite one character’s insistence that the mental damage is irreversible. At one point, after the deeply creepy Maximillian has murdered Kate’s crewmate, Reinhardt leans close to her and begs her to protect him from Maximillian. Is he mocking her? Is he living in constant terror of Maximillian, who might really be running this horror show? Wonderfully, the movie never tells us.

And then there’s this surreal closing scene, which is a perfect metaphor for Reinhardt’s ghoulish kingdom and an evocative, unsettling picture of a personal, self-created hell:

OK, so I’m in love with this film. But it’s certainly not perfect. What keeps it from greatness?

Professional critics have more than weighed in on it’s shortcomings already; I won’t dispute those critiques, but I can’t say that the commonly-cited problems (weak script, uneven acting, a continual contrast between the film’s exciting imagery and plodding dialogue) bothered me as much as they should’ve. I will point out a few things that kept me from wholly buying into The Black Hole despite my enjoyment of it:

1. The actions scenes are weak. It feels wrong to knock a movie for having insufficiently awesome action scenes, but the action scenes in this movie are universally unconvincing and unexciting. The evil sentry robots, described as an “elite” force at one point by Reinhardt, have worse aim than Stormtroopers—look, I know they’re not really supposed to hit anything or anybody important, but they have to look like they’re trying. There’s one large gun battle in particular that is so ineptly staged that it really damages the sense of immersion.

2. Reinhardt’s secret is too obvious and revealed too early. Look, we know Reinhardt’s an insane mad scientist, but the “big reveal”—what really happened to the crew—is telegraphed continually throughout the movie’s entire second act. When we finally get our confirmation, it’s lost most of its effectiveness.

3. The science is distractingly bad. For the first few minutes, it seems like The Black Hole is going to at least pay decent lip service to Real Science—enough to let us suspend our disbelief about all this black hole business. Nobody’s asking for Stephen Hawking levels of scientific integrity here. But the movie’s final act, which takes place while the Cygnus is being pulled inexorably into the black hole, throws all believability out the window. Characters breathe in open space. They outrun meteors. It’s really distracting.

Despite its flaws, this is a worthwhile film. I’m glad I finally mustered the courage to revisit this piece of childhood nostalgia, and I’m quite confident I’ll return to it again.

What’s the first thing you notice about this image, from an upcoming game called

What’s the first thing you notice about this image, from an upcoming game called

The portrayal of the Clone Wars in the Star Wars Episodes 1, 2, and 3 has long bothered me. Long, long ago, when I first watched Star Wars and heard crazy old Ben Kenobi’s offhand reference to the Clone Wars (in which he had served alongside Anakin Skywalker, the best starfighter pilot in the galaxy!), my young mind conjured up images of an epic conflict that ravaged the galaxy.

The portrayal of the Clone Wars in the Star Wars Episodes 1, 2, and 3 has long bothered me. Long, long ago, when I first watched Star Wars and heard crazy old Ben Kenobi’s offhand reference to the Clone Wars (in which he had served alongside Anakin Skywalker, the best starfighter pilot in the galaxy!), my young mind conjured up images of an epic conflict that ravaged the galaxy.