| What I thought my six-year-old daughter would learn in tae-kwon-do class | What she actually learned |

|---|---|

| The Way of the Exploding Fist | Report bullying behavior to a trusted adult |

| Death Before Dishonor | Never practice martial arts manuvers on a sibling or pet |

| Five Point Palm Exploding Heart Technique | Share with the class something kind you did this week, like you picked up your Legos without being asked or something |

| Foe-shaming Mantra of the Ineffable Bodhisvatta | It’s easier if you tie the right side of your uniform first |

| If You Meet the Buddha, Kill Him | We don’t use real weapons at this martial arts studio except for this one bo staff that is just for show and actually you’re not allowed near it |

| Drunken Master Style | Annual membership in the American Taekwondo Association costs how much?!? |

|

|

Category Archives: Parenting

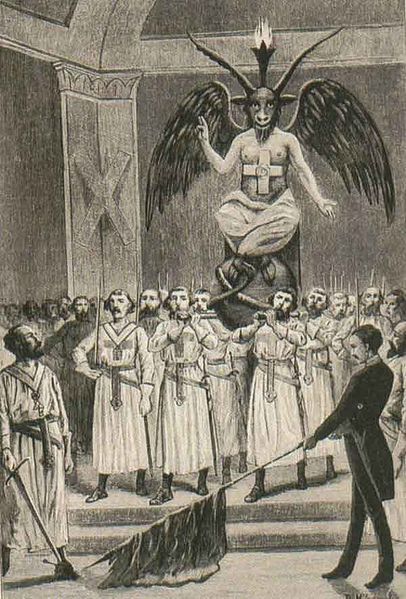

“Jacques de Molay, thou art avenged!”

Earlier this week, I was decluttering the basement, a task made more challenging by the fact that my five-year-old daughter had chosen to spread Adorable Kid Art™ all over the floor. It was going just fine, and the world made perfect sense, until I came across this page, apparently torn out of the most demented children’s coloring book in the Known Universe:

What the… who the… where I have seen this before? Oh, right:

The similarities are pretty clear. I don’t know who Baphomet is calling on that telephone there, but you know it’s not going to end well for the free world.

So apparently my daughter is a Templar. Or maybe a Freemason. (Jack Chick has a really great1 tract about the Freemasons and Baphomet, but I can’t bring myself to link to his website.)

Footnotes:

[1] crazy

An Illustrated Compendium of Monsters (for Four-Year-Olds)

Like every father of a four-year-old daughter, I’m called upon nightly to tell her bedtime stories. My daughter Thessaly insists that each night’s story be something she hasn’t heard before, so for years now I’ve been scrambling to come up with interesting tales.

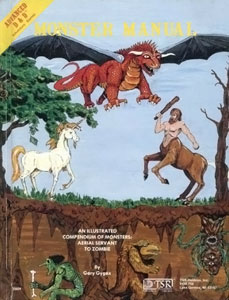

The 1st edition AD&D Monster Manual.

I realized early on that it was the villain of each story that really enchanted Thessaly. Whenever a bad guy would appear in the story, she wanted to know all about it: what did it look like, where did it live, what powers did it have, why was it acting so villainous. And at some point I realized that I could tap my Dungeons & Dragons obsession to make these stories more fun. So for the last few months, I’ve been using creatures from the Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual as the foes in these nightly stories.

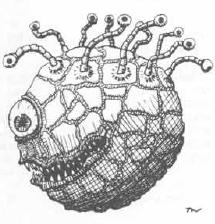

It’s worked out well, because the Monster Manual is full of bizarre and imaginative beasts. Here are some that have appeared in the nightly stories, with notes on how my daughter reacted:

Tarrasque: One night Thessaly insisted that the story’s villain be the biggest, strongest, scariest monster available, and in D&D, there’s one monster that truly meets that description: the tarrasque, a gargantuan apocalyptic terror. Despite its fearsomeness, Thessaly the Hero regularly exploits its lack of dexterity to defeat it. For whatever reason, the tarrasque is one of her favorites, and I regularly have to invent ways to bring it back for repeat appearances.

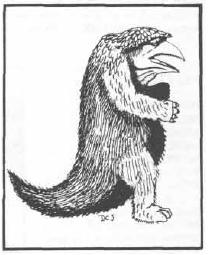

Yes, it’s the owlbear.

Gelatinous Cube: This mobile block of slime is an iconic D&D monster, and Thessaly loved it. She was so taken by the gelatinous cube, in fact, that she recruited it as a friend and it has made several guest appearances now as Thessaly the Hero’s sidekick.

Cockatrice: I don’t even remember what this one is, except that it’s, like, a rooster combined with some other type of creature. My lack of enthusiasm for this unfortunate beast was obvious and it hasn’t been missed since Thessaly the Hero jailed it a month or so ago.

Behold!

Blackbeard: OK, Blackbeard’s not a D&D monster, but he should be. He’s a definite Thessaly favorite and has escaped from prison nearly as many times as the tarrasque has. Blackbeard’s appearance on the scene has allowed me to expand the scope of the nightly stories to include oceanic scenarios.

Leviathan: I’m not sure if there’s a leviathan in D&D lore, but I needed an aquatic monster to follow up on the popularity of Blackbeard, and so was born the leviathan, watery sibling of the tarrasque. Frequently teams up with the tarrasque to menace society.

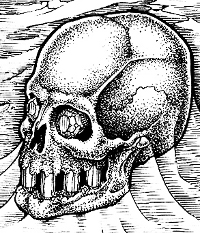

Yes, I know Acererak is technically a demi-lich, not a lich. I’m trying to keep things simple for my daughter until the day she grows up and learns the differences between types of undead wizard.

Cribbing bad guys from the Monster Manual has made me realize anew just how creative and entertaining many of the Monster Manual entries are; watching my daughter smile at the mental picture of a beholder or an umber hulk reminds me of what it was like to first flip through the pages of the AD&D Monster Manual as a kid.

With the variety of creatures in the Monster Manual—and the sheer number of monster books published over the years—I’m hoping this will last me until Thessaly tires of the format. And at this rate, I can tell several years’ worth of stories before I have to resort to incorporating the flumph….

Won’t you think of the (fictional) children?!

A lot of things in your life and attitude change when you become a parent. That is, of course, not exactly a brilliant insight for the ages. But I was unprepared for one minor but very definite change in myself that took place almost immediately upon the birth of our daughter three years ago: I became utterly unable to handle the sight, or even the thought, of a child’s suffering in books, movies, or the newspaper.

Before our daughter’s birth, my tastes in entertainment were pretty “mainstream American”—that is, jaded. While I didn’t enjoy the extreme end of cinematic violence, I could watch a Tarantino movie without flinching (much). I played ultra-violent video games. I approached fictional violence and death involving children the same way I approached violence and death involving adults: sometimes unpleasant, sometimes tear-jerking, but nothing that merited emotional investment beyond what the film’s (or book’s) narrative called for.

Then our wonderful, beautiful daughter was born.

I noticed the change a few months after that. My wife and I were watching an episode of The X-Files during one of those rare breaks in between infant care. In the episode, two young children—a toddler and a slightly older boy—are murdered by the villain. Nothing graphic; the deaths take place offscreen.

I can confidently say that before parenthood, this wouldn’t have bothered me in the slightest, beyond establishing that the bad guy was really bad. But I was physically shaken. I wanted to turn off the episode. Afterward, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. How impossibly cruel, to kill these fictional children! How impossibly painful for this fictional family!

Beyond being upset—something I could easily explain as anxiety about my own daughter’s safety—I felt something stronger: real anger and resentment toward the episode and its creators. On one level I was angry that the writers had successfully exploited my new emotional weakness. But I was actively angry just at the thought of somebody using the suffering and death of a child in something so tawdry as a TV show. I tried to imagine the sort of empty-souled shell of a human being that would use a child’s death (even a fictional one) as a mere plot device.

Since then, this emotional hot-button of mine has shown no signs of going away. I can’t watch or read even the mildest instance of cruelty or violence inflicted on a child without wanting to physically get up and leave… and punch the screenwriter/author. Just seeing a kid threatened with violence—say, by a villain trying to blackmail a movie’s protagonist—is enough to freak me out. The other day I actually threw a book down in anger, something I don’t think I’ve ever done before, when a character in the story cruelly hurt a child. When I read or watch such a thing, I wonder about how the fictional child’s fictional parents will ever cope; and now even when an adult is hurt or killed, I wonder if the fictional adult has fictional kids whose lives have just been ruined.

I had never really thought about how common it is to use threats against children to drive plots and increase suspense. Intellectually I don’t have a problem with that storytelling device, but these days I demand that there be a really good narrative reason for it.

I imagine this will fade a bit with time. But right now, I find myself avoiding movies, books, or video games where I even suspect a child may suffer.

I can understand why my mind has reached this point, but the suddenness and completeness of the change caught me off guard. And I should note that I don’t especially miss being jaded about this topic—it’d be nice to feel less emotional wimpy while watching movies and TV, but I’m not really interested in going back to being a person who didn’t bat an eyelash at the fictional portrayal of violence against kids.

It makes me wonder at all the other commonplace narrative setups—rape, domestic violence, murder, grief, loss of a loved one, etc.—that go right past me without registering but prey on the emotional vulnerabilities of people who’ve experienced them in real life.