The story: “Strawberry Spring,” collected in Night Shift. Originally published in 1968. Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A man recounts the strange events of a “strawberry spring” (like an Indian summer, but in the spring) years ago, when a serial killer murdered several women on a college campus but was never caught. The narrator’s reminiscing ends with his realization that he was, and still is, the killer.

My thoughts: As you’ve no doubt noticed by now, Stephen King has written novels and stories that draw on nearly every horror-story trope in existence. In a number of cases, he may have single-handedly popularized them. But curiously, one trope he hasn’t focused on heavily (to my knowledge) is the Serial Killer. (Another neglected trope is Zombies—you might be surprised to learn that they’re the centerpiece of his novel Cell, but not much else.)

King’s massive body of work doesn’t contain many serial killers. (Granted, his non-serial killer villains do nevertheless tend to kill lots and lots of people.) There’s Annie Wilkes from Misery, Bob Anderson in “A Good Marriage,” the narrator of “Strawberry Spring,” and no doubt a few others I’m forgetting. (King experts, please share in the comments below.) But given the popularity and glamorization of the Silence of the Lambs-style serial killer in thrillers and film these days, it’s a little unusual that very few of King’s villains fit the profile of the charming, witty, and intelligent psychopath compelled by dark urges to kill in disturbing fetishistic ways. King’s villains are often crazy, murderous, and charismatic, but not in the way we associate with serial killers as pop culture depicts them.

“Strawberry Spring” presents the recollections of a man who may not fully realize until the story’s end that he is, in fact, the killer known as “Springheel Jack.” During a short period of strange foggy weather that gave evenings a surreal and dreamlike quality, Springheel Jack terrorized a college campus by savagely killing several women.

King spends less time describing the murders than he does depicting the panicked, and increasingly irrational, public response to them—and this is what makes “Strawberry Spring” better than your typical serial killer story. King fancies himself a student of human nature and social behavior (in The Stand, characters spend a great deal of time hashing out social theory) and he gets it right here. He traces the college community’s reaction to the murders from its early stages (gossipy fascination with the murders and victims); to the more serious and coordinated attempts to solve the crimes (increased security, arrests, and a general atmosphere of tension); to the crazy phase (conspiracy theories spread like wildfire), to the inevitable end (public boredom, as the killings end and new distractions appear in newspaper headlines). It’s a response-to-tragedy pattern that is unfortunately very familiar to those of us in the United States at the moment.

“Strawberry Spring” closes with a surprise revelation, an element common in horror stories but very hit-and-miss in execution. It works well here because King has carefully pointed us toward the revelation (so it doesn’t seem random) without making it too obvious. There are enough clues spread through the story to make you feel smart for noticing them, like in a good mystery novel. Of course, you know you’re reading a story by Stephen King, so you’re somewhat on the alert for this sort of thing. But there’s also the vaguely confessional nature of the first-person narration; the fact that the narrator begs off of social functions to be alone on the nights of the murders; and the overly romantic way that the narrator describes the fog and other features of the strawberry spring nights.

I ended up enjoying this story much more than I thought I would. (I’m really not a fan of the serial killer genre.) And impressively for one of King’s early, obscure little stories, it features one of his very best closing lines:

I can hear my wife as I write this, in the next room, crying. She thinks I was with another woman last night.

And oh dear God, I think so too.

Next up: “Sorry, Right Number,” from Nightmares and Dreamscapes.

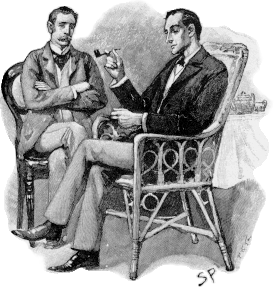

My thoughts: When Andy asked me to read Stephen King’s short story “The Doctor’s Case,” I was sure it would be too violent for me. I haven’t read anything by King since high school, but my vague recollections suggested to me that he wouldn’t be able to resist getting some gory details in some way or another. I was surprised to find that the extent of the gore consisted of the phrase “There was a dagger in his back.” I’m happy to say I rallied quickly from this assault upon my sensibilities.

My thoughts: When Andy asked me to read Stephen King’s short story “The Doctor’s Case,” I was sure it would be too violent for me. I haven’t read anything by King since high school, but my vague recollections suggested to me that he wouldn’t be able to resist getting some gory details in some way or another. I was surprised to find that the extent of the gore consisted of the phrase “There was a dagger in his back.” I’m happy to say I rallied quickly from this assault upon my sensibilities.  The story: “Trucks,” collected in Night Shift. First published in 1973.

The story: “Trucks,” collected in Night Shift. First published in 1973.  We never get an explanation for this automotive revolt, and the story doesn’t really need one. All we need to know is that every motor vehicle larger than a car is now possessed of a bloodthirsty cunning, and is working in coordination with other vehicles to kill us. The protagonists are a mostly forgettable collection of average Americans—a salesman, a trucker, a cook, some teenagers, and the anonymous narrator—and they follow the horror-survival script closely as they hunker in a diner, watching malevolent semi trucks circle the property. The salesman snaps and makes an ill-advised break for freedom (and dies badly); the narrator tries to rally the others to make longer-term survival plans. After a few more characters are killed, the true horror of the situation becomes clear: the trucks—implied now to have free reign across all of America, and whose ranks now include not only semis but construction vehicles, tractors, and possibly even aircraft—intend for the humans to be their slaves, refueling and maintaining the vehicles in exchange for their lives.

We never get an explanation for this automotive revolt, and the story doesn’t really need one. All we need to know is that every motor vehicle larger than a car is now possessed of a bloodthirsty cunning, and is working in coordination with other vehicles to kill us. The protagonists are a mostly forgettable collection of average Americans—a salesman, a trucker, a cook, some teenagers, and the anonymous narrator—and they follow the horror-survival script closely as they hunker in a diner, watching malevolent semi trucks circle the property. The salesman snaps and makes an ill-advised break for freedom (and dies badly); the narrator tries to rally the others to make longer-term survival plans. After a few more characters are killed, the true horror of the situation becomes clear: the trucks—implied now to have free reign across all of America, and whose ranks now include not only semis but construction vehicles, tractors, and possibly even aircraft—intend for the humans to be their slaves, refueling and maintaining the vehicles in exchange for their lives. So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently.

So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently. Spoiler-filled synopsis: A man diagnosed with terminal cancer makes a deal with the devil: he’ll get better if he designates somebody else who will suffer in his place. He designates his “best friend,” whom he secretly hates, and enjoys a long, healthy life while his friend’s life falls apart.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A man diagnosed with terminal cancer makes a deal with the devil: he’ll get better if he designates somebody else who will suffer in his place. He designates his “best friend,” whom he secretly hates, and enjoys a long, healthy life while his friend’s life falls apart.