Hey, ‘net punk! Look what some clever console cowboy has revealed on the inter-tron today:

OK, so it’s just a video game. But this is a kind of a big deal if you’re into tabletop roleplaying games, because this is a video game based on Mike Pondsmith’s venerable Cyberpunk 2013 (later Cyberpunk 2020, later Cyberpunk 203X) roleplaying game setting.

And that’s interesting for a number of reasons. First, the Cyberpunk RPG is an oldie, firmly planted in the mirrorshades era of the cyberpunk genre; the kind of cyberpunk where you brush aside your ’80s bangs and “jack in” to a Gibsonesque (and by “Gibsonesque” I mean “ripped straight out of Neuromancer“) proto-internet and talk sneeringly about “meatbags.” There are “fresher” cyber-themed RPGs out there (Eclipse Phase, Shadowrun, Transhuman Space) that might be thought to offer a nicely updated cyberpunkish basis for a modern game.

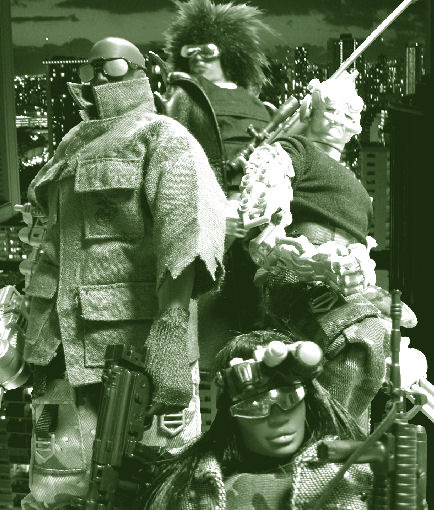

Pondsmith’s Cyberpunk hasn’t been much in the public eye for years. The last time it was the focus of any attention, its most recent edition was being dragged over the coals for using what can only be described as “doll art” to illustrate its rulebook:

Let’s just say that it didn’t emerge from those discussions with a lot of dignity intact.

But I don’t mean to mock. (Let me go on record as believing that the “doll art” thing contains a seed of genius, but was badly executed.) This new Cyberpunk video game is a reminder that there is a long history of tabletop RPGs—even obscure and mostly defunct ones like Cyberpunk—that are ripe for reinvention and re-exploration, in video games or other media. That’s exciting.

So let me offer a few comments on the Cyberpunk 2077 trailer above.

- The “2077” is presumably a reference to the year in which the game is set. Interesting; I believe that Shadowrun, the most prominent cyberpunk RPG still in print, is also currently set in the 2070s. I guess that “50-60 years from now” is about what seems right for a setting that needs to have advanced significantly beyond current technology levels, but not so far that it isn’t recognizeable and relatable.

- This game follows on the very popular cyberpunk video game Deus Ex: Human Revolution. Is vintage cyberpunk making a comeback?

- The technical quality of this trailer—the animation style, the music, everything—points to a pretty spectacular end-product.

- The lady in this trailer isn’t dressed very appropriately for a dangerous nighttime urban dystopian environment; but then again, she’s got the retractable arm-scythes, so she can wear what she wants. The future is cheesecake.

- I’ll expand on that a bit. The association of eroticism with violence in entertainment media, such as this video game trailer, makes me uncomfortable, but I’ll concede that I’m probably a few decades too late to raise that particular concern (and it’s been a staple of cyberpunk since Ghost in the Shell and probably earlier). I will say: the cyberpunk genre is about a future defined by out-of-control marketing of all types (including sexual) and the augmentation of the human body, so in theory there are some interesting, and possibly even prescient, points to be made about violence, sexuality, and the ultimate victory of style over substance. But I’m not holding my breath that this video game is where we’ll see that handled with insight.

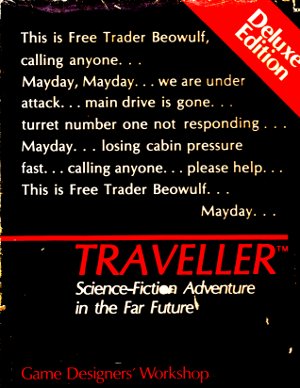

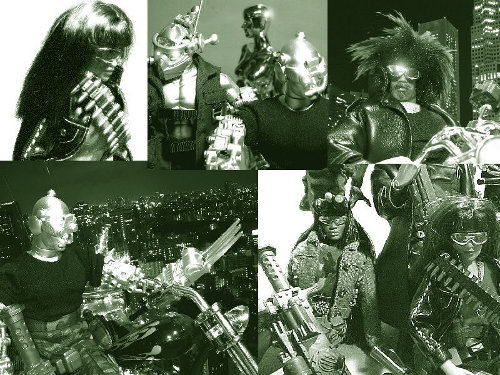

Well, we’ll see where this all winds up. But we can be sure it won’t top this artifact from the glory days of cyberpunk gaming:

Hey, look! A new version of the vintage Rolemaster RPG is out, and they’ve released

Hey, look! A new version of the vintage Rolemaster RPG is out, and they’ve released