The story: “All That You Love Will Be Carried Away,” collected in Everything’s Eventual. First published in 2001. Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A travelling salesman checks into a hotel in rural Nebraska intending to kill himself. However, his desire to pursue an unusual hobby/obsession just might be strong enough to keep him alive. The story ends ambiguously, leaving us unsure about his ultimate fate.

My thoughts: This is an odd, somber story. It’s somber because it immerses us in the mental state of a man contemplating suicide. It’s odd because the hobby that might give this man the strength to go on living is a bizarre one: he obsessively records bathroom-wall graffiti from public restrooms all around America. This is certainly not the first time that King has tenuously balanced a serious topic with a borderline bad-taste gimmick in the same tale. But he has a way of making these things work.

The focus on suicide makes me wonder what I would have made of this story had I encountered it during my big Stephen King obsession back in late high school and early college. At the time, I was writing mopey, overly-earnest short stories that involved a lot of death, suicide, and self-sacrifice; while I certainly wouldn’t have suggested that suicide was a good thing, it had a sort of romantic ring to it. (You can blame a too-young reading of The Sorrows of Young Werther. Or maybe Shōgun.) Today, however, with many years between me and my immature teenage self, it’s just a terribly sad thing to ponder. Not knowing where King was going with the topic, and not entirely trusting him to treat it with delicacy (the bathroom-graffiti sideplot didn’t help), I read this story nervously.

I’m relieved and happy to have been wrong, though. King’s empathy for Alfie, the suicidal salesman, is palpable. Alfie’s suicidal thoughts aren’t prompted by a single failure or point of shame, but rather by the accumulated weight of a life that has lost purpose. But Alfie is a good man and we desperately want him to pull through. I imagine that most authors can be said to “love” their invented characters, but read a few King tales and I think you’ll agree with me when I say that King goes a step further—he’s often actively rooting for his characters. Even the bad ones! (Look at King’s obvious love for the incredibly varied cast of The Stand, for instance.) For this reason, even though this story ends with the possibility that Alfie will go on to kill himself, you’re left with a very strong hunch that it’s going to be OK. Why wouldn’t we feel this way when the story itself seems to want Alfie to live?

So let’s talk about that bizarre hobby of Alfie’s: he records bathroom graffiti. Obscene limericks, lowbrow witticisms, incoherent pronouncements, and cries for help—Alfie records it all in his notebook, and over time starts to feel that he’s put his finger on the pulse of a dark, hidden, fascinating undercurrent of raw humanity. Alfie dissects the grammar of insane rants; he critiques the meter of dirty poems; he mulls over particularly compelling phrases. I expected at first that Alfie’s hobby was giving him a glimpse into what would prove to be some kind of supernatural, occult underworld lurking beneath the surface of American society; but King doesn’t go in that direction. Instead Alfie seems to have found a window into America’s clever, crazy, base, and 100% human collective id.

The very weirdness of this hobby might be what saves Alfie in the end—he delays suicide several times because he doesn’t want the police to find his graffiti journal and conclude that he was just crazy.

In his nonfiction writing, King has often sighed about the kinds of questions his fans direct at him, most especially “Where do you get your ideas?” But many King story ideas can be seen to originate in “everyday stuff you bump into as you go through life”—mundane things like road construction or graffiti. Whereas you and I have trained our minds to disregard the petty, routine details of everyday life, King is always on the lookout for ways to fit a story around them.

And need I mention that this story gives King a perfect excuse to recite a lot of dirty limericks that he’s clearly proud of? Admit it—that’d be pretty fun.

Next up: “The Reaper’s Image,” in Skeleton Crew.

My thoughts: Ah, revenge—the dish best served cold. “Dolan’s Cadillac” is a straightfoward and mostly satisfying story of long-delayed revenge, with almost no hint of the supernatural. In my last King short story writeup two years ago (

My thoughts: Ah, revenge—the dish best served cold. “Dolan’s Cadillac” is a straightfoward and mostly satisfying story of long-delayed revenge, with almost no hint of the supernatural. In my last King short story writeup two years ago ( Two years ago, I spent the month of October

Two years ago, I spent the month of October

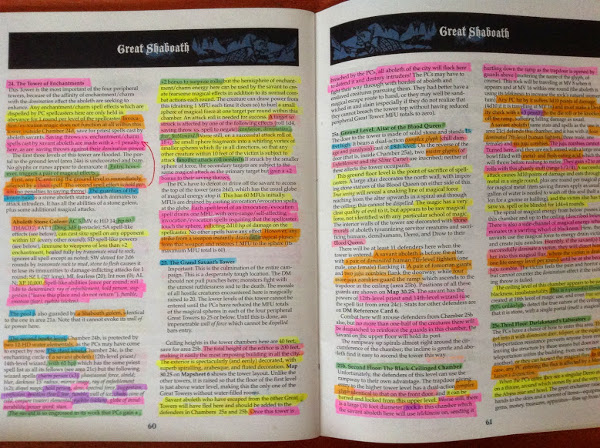

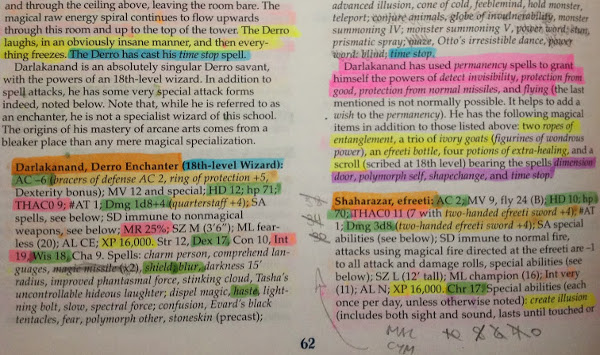

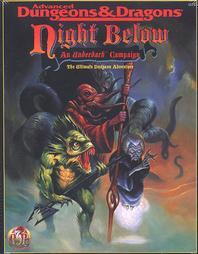

And having provided hundreds of hours of collective entertainment, how did this boxed set wind up being sold on the internet for a few measly bucks? Surely there’s a story there too, of a hobby abandoned, a game group graduating and getting married and heading to different corners of the country, a family clearing out a garage storage bin after a death, or whatever else you might imagine.

And having provided hundreds of hours of collective entertainment, how did this boxed set wind up being sold on the internet for a few measly bucks? Surely there’s a story there too, of a hobby abandoned, a game group graduating and getting married and heading to different corners of the country, a family clearing out a garage storage bin after a death, or whatever else you might imagine.

My thoughts: It’s occurred to me more than once this month, as I’ve made my way through King’s short stories, that King’s writing strength is in suspense as much as horror. There are certainly exceptions, and obviously the two genres have a lot in common—a good horror story usually involves a lot of suspense. But I’d venture to say that King is at least as good at writing non-supernatural suspense as he is at writing scenes of supernatural terror. In non-supernatural stories like “In the Deathroom,” “Survivor Type,” and this one, he ratchets up the tension quite effectively without calling in the ghosts and goblins.

My thoughts: It’s occurred to me more than once this month, as I’ve made my way through King’s short stories, that King’s writing strength is in suspense as much as horror. There are certainly exceptions, and obviously the two genres have a lot in common—a good horror story usually involves a lot of suspense. But I’d venture to say that King is at least as good at writing non-supernatural suspense as he is at writing scenes of supernatural terror. In non-supernatural stories like “In the Deathroom,” “Survivor Type,” and this one, he ratchets up the tension quite effectively without calling in the ghosts and goblins. Spoiler-filled synopsis: Years after he took part in a space mission to Venus, a crippled astronaut discovers that a hostile alien presence is using him as a “doorway” through which to observe Earth. This is manifested in the appearance of alien eyes on his hands. As the aliens’ influence over the astronaut’s body grows, he is forced to use extreme measures—self-mutiliation and ultimately suicide—to close the “doorway.”

Spoiler-filled synopsis: Years after he took part in a space mission to Venus, a crippled astronaut discovers that a hostile alien presence is using him as a “doorway” through which to observe Earth. This is manifested in the appearance of alien eyes on his hands. As the aliens’ influence over the astronaut’s body grows, he is forced to use extreme measures—self-mutiliation and ultimately suicide—to close the “doorway.” My thoughts: “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut” isn’t a horror story—it’s a “let me tell you about something weird I once saw” campfire tale, told in the form of an old man’s reminiscences. There’s no gore or violence to be found, and it has a happy ending—it’s almost sweet. It’s wistful and maybe a little melancholy, but in a pleasant way.

My thoughts: “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut” isn’t a horror story—it’s a “let me tell you about something weird I once saw” campfire tale, told in the form of an old man’s reminiscences. There’s no gore or violence to be found, and it has a happy ending—it’s almost sweet. It’s wistful and maybe a little melancholy, but in a pleasant way.