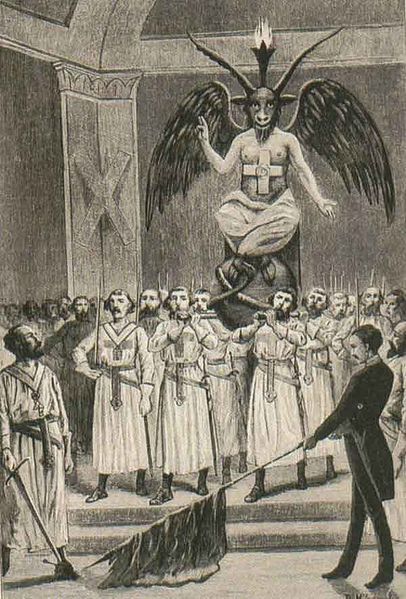

A typical H.P. Lovecraft horror.

Spoiler-filled synposis: A 19th-century gentleman inherits a family estate near the shunned and abandoned town of Jerusalem’s Lot. After a series of escalating supernatural encounters, he learns that he is the last living member of a bloodline damned long ago by its association with a Lovecraftian horror. He spirals into madness and (it’s implied) kills himself to end the family curse.

My thoughts: “Jerusalem’s Lot” is a rare curiousity in the King library: a straight-up pastiche of H.P. Lovecraft. The writing style mirrors Lovecraft’s reasonably closely, and the story itself is an amalgam of several classic Lovecraft tales, most notably “The Dunwich Horror” and “The Rats in the Walls”. It incorporates almost all of the Lovecraft elements: tainted ancestry, rural New England, blasphemous tomes, inexorable descents into madness, mind-shattering revelations about the nature of reality, and (of course) cosmic horrors with unpronounceable names.

And “Jerusalem’s Lot” is a pretty decent homage—not on par with Lovecraft’s best work (since it’s basically just copying those stories), but better than Lovecraft’s weaker efforts. It has two major weaknesses: 1) it falls short of Lovecraft’s feverishly overblown vocabulary of horror; and 2) it is content to recycle Lovecraftian plots and story elements without adding anything new. Readers who aren’t familiar with Lovecraft (as I was not when I first read it) might find “Jerusalem’s Lot” unsettling and compelling. Readers who know their Lovecraft will find this story enjoyable, but in a quaint sort of way.

It’s interesting to me that outside of this story and perhaps one other (“Crouch End,” which we may get to later), King steers clear of overtly Lovecraftian tales. That is not to say that Lovecraftian elements do not crop up; Lovecraft’s influence on modern horror is immense, and King clearly appreciates that. Many of King’s tales contain villains that could be described as somewhat Lovecraftian. But King has never seemed especially interested in the baroque occult trappings of the Lovecraft mythos.

Why is that? I suspect that King simply likes evil that is personal rather than cosmic. Lovecraft’s evil gods are profoundly inhuman and impersonal; they’re malevolent forces of nature, not enemies you can love to hate. King’s bad guys, by contrast, are often quirky and “human” to the extreme. King prefers his villains cruel, petty, and believable. When Lovecraftian threats are present, as in “The Mist,” King usually provides a more recognizably human villain to serve as the story’s primary obstacle. Even King’s most seemingly Lovecraftian villain, the ancient, near-omnipotent “Pennywise” from It, spends most of its time mocking the insecurities of a band of awkward teenage nerds. What evokes a greater emotional response in you: the idea of a distant, uncaring alien demon (and the nihilistic atheism it implies), or the brutal schoolyard bully who makes your everyday life a living hell? King thinks it’s the latter. He likes villains with personalities, and personalities are not much on display in Lovecraft’s nameless gods, insane cultists, and alien monsters.

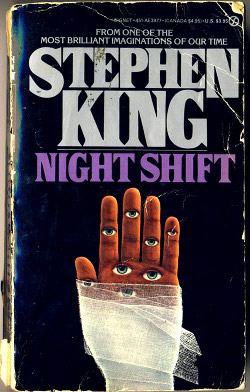

Which makes this story all the more fun for being (nearly) unique in the King library. Through either deliberate care or simple inexperience (according to Wikipedia, King wrote “Jerusalem’s Lot” in college), King paints very meticulously within Lovecraft’s lines, with few diversions into recognizeably “Stephen King” territory. Which makes for an enteratining story, but perhaps not what you were hoping for when you picked up Night Shift looking to read, you know, a Stephen King story.

One final note: although King’s novel ‘Salem’s Lot shares a setting with “Jerusalem’s Lot,” there’s no explicit connection between the short story and the novel beyond the location. In “Jerusalem’s Lot,” the evil is a degenerate cult and its monstrous deity; in ‘Salem’s Lot the problem is vampires. I like that King doesn’t feel the need to tie these more closely together. Jerusalem’s Lot is a clear example of one of his favorite themes: the “bad place,” a geographic location that attracts darkness and evil for no clear reason. The narrator of “Jerusalem’s Lot” describes this King trope well:

I believe… that there are spiritually noxious places, where the milk of the cosmos has become sour and rancid.

Next up: “Fair Extension,” from Full Dark, No Stars.

But moving along: after wandering lost a while (this story takes place before cellphones and GPS devices were commonplace or even imaginable), the two stumble across a picturesque, nostalgic little all-American town with the cutesy name of “Rock and Roll Heaven,” planted inexplicably in the middle of a huge creepy forest wilderness. King often allows his protagonists a certain meta-awareness of their horror-story plights; Mary immediately recognizes that the too-perfect town is creepy as heck, and even mentions its evocation of Twilight Zone episodes and Ray Bradbury stories.

But moving along: after wandering lost a while (this story takes place before cellphones and GPS devices were commonplace or even imaginable), the two stumble across a picturesque, nostalgic little all-American town with the cutesy name of “Rock and Roll Heaven,” planted inexplicably in the middle of a huge creepy forest wilderness. King often allows his protagonists a certain meta-awareness of their horror-story plights; Mary immediately recognizes that the too-perfect town is creepy as heck, and even mentions its evocation of Twilight Zone episodes and Ray Bradbury stories. Every year when Halloween looms on the horizon, I find myself in the mood for scary stuff. In past Octobers, I’ve made a point of watching horror movies, playing horror-themed boardgames, or reading spooky books.

Every year when Halloween looms on the horizon, I find myself in the mood for scary stuff. In past Octobers, I’ve made a point of watching horror movies, playing horror-themed boardgames, or reading spooky books.

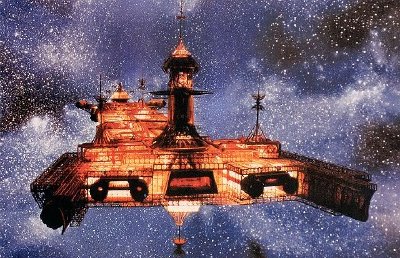

I just watched The Black Hole with Michele. I haven’t watched it in probably twenty years, but it’s always held an extremely powerful nostalgic pull on my imagination. When I was a kid, I went through a period of obsession with this film—we’re talking a

I just watched The Black Hole with Michele. I haven’t watched it in probably twenty years, but it’s always held an extremely powerful nostalgic pull on my imagination. When I was a kid, I went through a period of obsession with this film—we’re talking a  3. It’s weird and dark, with lots of unnerving details. The “robot” unmasking scene scarred me for life as a child, and it retains some of its shock value today even though it’s obviously a guy in makeup. The “robot” funeral leaves you wondering uncomfortably how much humanity might still lie buried away, despite one character’s insistence that the mental damage is irreversible. At one point, after the deeply creepy Maximillian has murdered Kate’s crewmate, Reinhardt leans close to her and begs her to protect him from Maximillian. Is he mocking her? Is he living in constant terror of Maximillian, who might really be running this horror show? Wonderfully, the movie never tells us.

3. It’s weird and dark, with lots of unnerving details. The “robot” unmasking scene scarred me for life as a child, and it retains some of its shock value today even though it’s obviously a guy in makeup. The “robot” funeral leaves you wondering uncomfortably how much humanity might still lie buried away, despite one character’s insistence that the mental damage is irreversible. At one point, after the deeply creepy Maximillian has murdered Kate’s crewmate, Reinhardt leans close to her and begs her to protect him from Maximillian. Is he mocking her? Is he living in constant terror of Maximillian, who might really be running this horror show? Wonderfully, the movie never tells us.

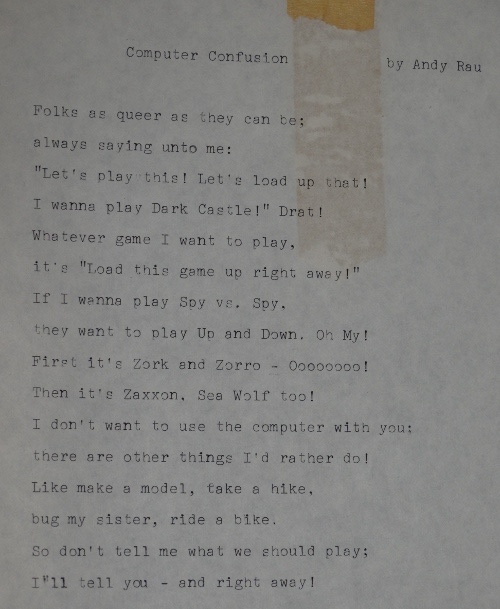

One of the most-read books in my game library when I was in junior high and high school was

One of the most-read books in my game library when I was in junior high and high school was