The story: “The Raft,” collected in Skeleton Crew. First published in 1982. Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synposis: Four college students pay a visit to an isolated, tranquil lake to live up the last days of summer. Alas, they’re trapped out on the lake by a strange creature and are killed off one by one in excessively gruesome ways.

My thoughts: Ewwwwwwww.

I suspect this is what people who haven’t read Stephen King’s work, imagine that all Stephen King’s work is like: weird, lurid, and horrifying.

So far in this little October short story project, we’ve read Stephen King short stories that fit a number of classic horror sub-genres: we’ve seen the Lost Travellers and the Town with a Dark Secret; Lovecraftian Horror; the Faustian Bargain; and the Three Wishes. “The Raft” fits neatly into another familiar theme: Hormone-Addled Teenagers Engage in Forbidden Activities and Die Horribly.

The first few pages of this story are spent getting to know our doomed protagonists: Randy (the nerd), Deke (the jock), Rachel (the sweet girl), and LaVerne (the mean girl). As I’ve noted in discussing other stories, King writes personal interaction well, and he’s got his finger on the pulse of teenage social dynamics. Even as horror envelops the protagonists, they’re evaluating relationships, competing for social status, and thinking about sex. In the brief time we have to get to know these kids, Randy and Rachel come across as the most sympathetic; Deke isn’t a villain, but he’s got a streak of the Stephen King “bully” archetype running through him, and LaVerne comes across as a bit of a boyfriend-stealing jerk.

Actually, it’s the portrayal of the two women in this story that stands out most strongly to me, reading it now. To put it bluntly: there is a weird and uncharacteristic amount of violence directed at the women in “The Raft.” I do understand the rather over-the-top situation they’re in, what with the flesh-eating oil-slick monster that has them trapped in the middle of the lake. But it’s nonetheless not very fun to read about male characters either striking, or thinking about striking, the women, one of whom dies early in the story and the other of whom is quickly reduced to a gibbering, fainting wreck. All of the characters, but especially the women, lack agency; with little prospect of escape, they’re mostly just passive victims. This seems a bit out of character for King, who is actually known for his strong female characters to the point that several of his later books could probably be described as feminist empowerment tales. “The Raft” is not really long enough for me to figure out whether King’s doing something deliberate with genre conventions or is simply being thoughtless here.

And of course, that violence all seems rather moot in the grand scheme of things. Three of the four protagonists are snared by the monster and die awful, luridly-described deaths; one of them is, in my opinion, one of the most gruesome deaths to be found in any King story or novel. (The fourth death, that of the narrator, is strongly implied but not described in the story’s final sentences.)

Apart from the over-the-top violence and the treatment of the female characters, one other element of “The Raft” stands out. If you’ve read much Stephen King, you’re certainly familiar with one of his trademark writing gimmicks—the use of italicized, parenthetical text to communicate what his characters are

(subconsciously thinking)

subconsciously thinking. While King sometimes over-uses this trick, it works reasonably well, and is effective here in supplying an otherwise trashy story with a bit of emotional weight. The curious phrase (do you love) pops up here, as it does in one or two other places in King’s work, as Randy, left alone at the end, contemplates his inevitable fate.

Apart from this, I don’t have much else to say about “The Raft.” It’s gross, it’s lurid… and it works alright. Certainly it works well enough that 20 years after I first read it, I could vividly remember the exact manner of Deke’s death. I wouldn’t recommend this story to somebody exploring King’s stories for the first time, but it does represent a strain of King’s writing that you’ll eventually want to confront.

Next up: “Trucks,” from Night Shift.

So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently.

So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently. Spoiler-filled synopsis: A man diagnosed with terminal cancer makes a deal with the devil: he’ll get better if he designates somebody else who will suffer in his place. He designates his “best friend,” whom he secretly hates, and enjoys a long, healthy life while his friend’s life falls apart.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A man diagnosed with terminal cancer makes a deal with the devil: he’ll get better if he designates somebody else who will suffer in his place. He designates his “best friend,” whom he secretly hates, and enjoys a long, healthy life while his friend’s life falls apart.

But moving along: after wandering lost a while (this story takes place before cellphones and GPS devices were commonplace or even imaginable), the two stumble across a picturesque, nostalgic little all-American town with the cutesy name of “Rock and Roll Heaven,” planted inexplicably in the middle of a huge creepy forest wilderness. King often allows his protagonists a certain meta-awareness of their horror-story plights; Mary immediately recognizes that the too-perfect town is creepy as heck, and even mentions its evocation of Twilight Zone episodes and Ray Bradbury stories.

But moving along: after wandering lost a while (this story takes place before cellphones and GPS devices were commonplace or even imaginable), the two stumble across a picturesque, nostalgic little all-American town with the cutesy name of “Rock and Roll Heaven,” planted inexplicably in the middle of a huge creepy forest wilderness. King often allows his protagonists a certain meta-awareness of their horror-story plights; Mary immediately recognizes that the too-perfect town is creepy as heck, and even mentions its evocation of Twilight Zone episodes and Ray Bradbury stories. Every year when Halloween looms on the horizon, I find myself in the mood for scary stuff. In past Octobers, I’ve made a point of watching horror movies, playing horror-themed boardgames, or reading spooky books.

Every year when Halloween looms on the horizon, I find myself in the mood for scary stuff. In past Octobers, I’ve made a point of watching horror movies, playing horror-themed boardgames, or reading spooky books.

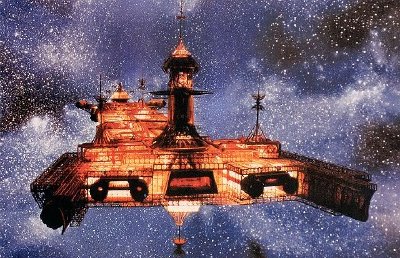

I just watched The Black Hole with Michele. I haven’t watched it in probably twenty years, but it’s always held an extremely powerful nostalgic pull on my imagination. When I was a kid, I went through a period of obsession with this film—we’re talking a

I just watched The Black Hole with Michele. I haven’t watched it in probably twenty years, but it’s always held an extremely powerful nostalgic pull on my imagination. When I was a kid, I went through a period of obsession with this film—we’re talking a  3. It’s weird and dark, with lots of unnerving details. The “robot” unmasking scene scarred me for life as a child, and it retains some of its shock value today even though it’s obviously a guy in makeup. The “robot” funeral leaves you wondering uncomfortably how much humanity might still lie buried away, despite one character’s insistence that the mental damage is irreversible. At one point, after the deeply creepy Maximillian has murdered Kate’s crewmate, Reinhardt leans close to her and begs her to protect him from Maximillian. Is he mocking her? Is he living in constant terror of Maximillian, who might really be running this horror show? Wonderfully, the movie never tells us.

3. It’s weird and dark, with lots of unnerving details. The “robot” unmasking scene scarred me for life as a child, and it retains some of its shock value today even though it’s obviously a guy in makeup. The “robot” funeral leaves you wondering uncomfortably how much humanity might still lie buried away, despite one character’s insistence that the mental damage is irreversible. At one point, after the deeply creepy Maximillian has murdered Kate’s crewmate, Reinhardt leans close to her and begs her to protect him from Maximillian. Is he mocking her? Is he living in constant terror of Maximillian, who might really be running this horror show? Wonderfully, the movie never tells us.