Been a while, eh? I bet you’re interested in what video games I’ve been playing. Well, you’ve talked me into it.

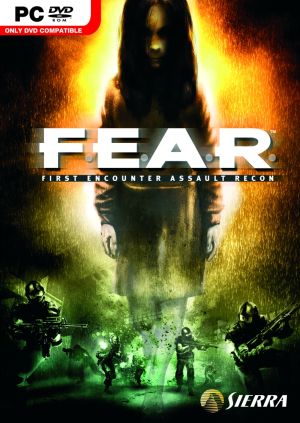

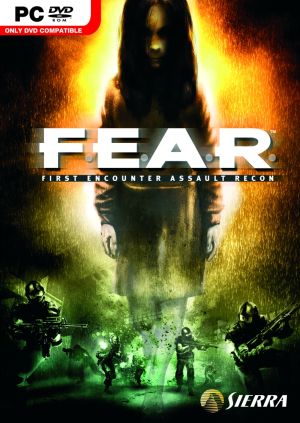

In my spare time, I’ve been playing through an old—and it pains me to use that adjective to describe a game released in 2005, which seems like it was just yesterday—first-person shooter called F.E.A.R. (with the periods; it’s an abbreviation for something). F.E.A.R. combines the venerable first-person shooter genre with the J-horror “scary long-haired girl” genre. So it’s like The Grudge, if Sarah Michelle Gellar had an AR-15 and was being constantly attacked by evil clone troopers.

It could be worse. You could be working for N.E.R.V.O.U.S.

It’s a neat game; it’s kinda scary, and the gun battles are fun in a way that I hope real-life gun battles are not. But one thing really stands out as meriting comment:

the Flashlight.

You see, much of the game takes place in creepy, poorly-lit environments from which scary stuff is frequently jumping out at you. In some areas the lighting is so dim (or non-existent) that you cannot see at all. Fortunately, the game has a solution: you have been equipped with a Flashlight.

But not just any flashlight. You see, your flashlight has 20 seconds of battery life before it switches off and must be recharged, a process that takes about 5 seconds. So travelling through dark areas is a matter of racing forward while your flashlight battery drains, then standing still for a few seconds while it recharges; at which point you switch it back on and move forward for 20 more seconds.

One understands the design motive behind this gameplay device. To make sure you spend at least some of the game in the scary dark, illumination is treated as a somewhat limited resource. Doom 3, which came out a few years before F.E.A.R. and relied on a similarly shadowy environment to creep you out, did something similar and was roundly mocked for its solution: you can have your flashlight out, or you could have a weapon out, but not both at the same time. I didn’t mind this tradeoff too much as it forced some tough choices every now and then (and really, I’m OK with not being able to wield a plasma cannon in one hand a flashlight in the other); but it’s hard to argue against the typical gamer complaints: if you’re such a bad-ass space marine, why don’t you just duct-tape the flashlight to the barrel of your gun? Or hold it in your teeth like they do in Hollywood movies? Or tie it to your helmet?

Why, indeed. F.E.A.R.‘s attempt to make turning on your flashlight a tactical dilemma is even worse, though. You’re a high-tech commando employed by some awesome secret agency, and you can’t get a flashlight that lasts more than 20 seconds? That is the worst flashlight ever. Let’s be honest: my 4-year-old daughter has a plastic flashlight shaped like a bee that diffuses its quickening ray from the “bee’s” rump, and it’s a more practical flashlight than the one they give you in F.E.A.R.

Pre-order F.E.A.R. 4 from Gamestop and get the limited edition KR-31 "Killer Bee" flashlight with which you can illuminate all your foes.

It’s an interesting game design problem, though. Like most FPS games, F.E.A.R. proudly boasts an extremely detailed and realistic environment. Buildings look and are laid out like real-life buildings. Your guns behave in a way that your typical basement-dwelling game nerd would consider realistic. Bullets knock nicely detailed chunks of concrete out of walls and shatter windows; rooms fill with blinding gunsmoke after lengthy gun battles. All of the graphics and combat mechanics work overtime to be as life-like and immersive as possible.

Yet it’s also fun to force the player travel through scary areas without reliable illumination. And so in the specific case of your flashlight, the game chucks immersion to the wind and gives you a wonky lightstick that has to be “recharged” every few seconds, because that’s more fun.

You can have realistic and immersive, or you can have gamey and fun; but when both are present in the same game, it’s a big distraction.

I’m reminded of an excellent essay on the lasting appeal of the original Doom, which had infinitely less believable environments but which turned that into a virtue:

While some of Doom’s levels have a very thin fiction via their title (eg “Hangar”) and general texturing theme, if you actually explore them you find they only resemble real locations in the loosest sense possible. This is precisely what allowed Doom’s level design to present a wide variety of interesting tactical setups. Level designers didn’t have to worry about whether a change made something look less like a hangar or a barracks, just whether it was better for gameplay. This was especially critical for a style of game that was just finding its feet in 1993.

As the march of technology has allowed ever-higher graphical fidelity, virtually every FPS since Doom has attempted greater and greater representationalism with its environments. While games like System Shock began to show that a real sense of place can be a huge draw in itself, designers of such games will always have to manage the tension between compelling fiction and optimal function, unless you are willing to go all out and have the kind of weird, abstract spaces Doom has. I would love to see more modern games break with this conventional wisdom and see where it leads, if only in an indie or experimental context.

F.E.A.R. is fun and elaborately crafted. But so was Doom, and Doom didn’t feel obliged to painstakingly recreate entire office blocks. Doom threw together a minotaur maze, slapped blinking lights on the walls, and called the level “Nuclear Plant.”

Now if you’ll excuse me, my flashlight is fully recharged and I’ve got to get back to the shooting.

by

by