Like every father of a four-year-old daughter, I’m called upon nightly to tell her bedtime stories. My daughter Thessaly insists that each night’s story be something she hasn’t heard before, so for years now I’ve been scrambling to come up with interesting tales.

The 1st edition AD&D Monster Manual.

Fortunately for me, the stories she wants to hear follow the same general pattern: a villain or monster shows up, threatening somebody or sometimes stealing a piece of treasure; the rightful authorities (usually Mommy and Daddy) attempt to fight the bad guy but get in over their heads and have to call in backup, in the person of Thessaly the Hero. (Thessaly the Hero is my daughter plus magic powers, serving here as a rather blatant

Mary Sue character.) Thessaly then tricks, subdues, or imprisons the villain using cleverness or occasionally a magic power.

I realized early on that it was the villain of each story that really enchanted Thessaly. Whenever a bad guy would appear in the story, she wanted to know all about it: what did it look like, where did it live, what powers did it have, why was it acting so villainous. And at some point I realized that I could tap my Dungeons & Dragons obsession to make these stories more fun. So for the last few months, I’ve been using creatures from the Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual as the foes in these nightly stories.

It’s worked out well, because the Monster Manual is full of bizarre and imaginative beasts. Here are some that have appeared in the nightly stories, with notes on how my daughter reacted:

Tarrasque: One night Thessaly insisted that the story’s villain be the biggest, strongest, scariest monster available, and in D&D, there’s one monster that truly meets that description: the tarrasque, a gargantuan apocalyptic terror. Despite its fearsomeness, Thessaly the Hero regularly exploits its lack of dexterity to defeat it. For whatever reason, the tarrasque is one of her favorites, and I regularly have to invent ways to bring it back for repeat appearances.

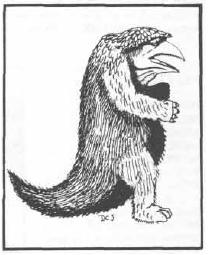

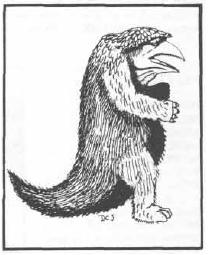

Yes, it’s the owlbear.

I expected this one to be a huge hit, because it’s, you know, a bear with the head of an owl. That has “kids will love it” written all over it, right? But for whatever reason, the owlbear was a complete dud, and Thessaly’s never requested its return. Admittedly, it was difficult to come up with a compelling villainous motive for a giant owl-headed bear beyond general ornery-ness.

Gelatinous Cube: This mobile block of slime is an iconic D&D monster, and Thessaly loved it. She was so taken by the gelatinous cube, in fact, that she recruited it as a friend and it has made several guest appearances now as Thessaly the Hero’s sidekick.

Cockatrice: I don’t even remember what this one is, except that it’s, like, a rooster combined with some other type of creature. My lack of enthusiasm for this unfortunate beast was obvious and it hasn’t been missed since Thessaly the Hero jailed it a month or so ago.

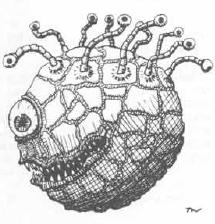

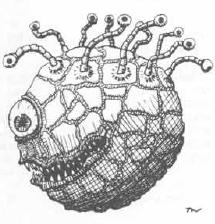

Behold!

A floating mouth with a dozen eyestalks—what’s not to love? The beholder was popular for several stories due to the increasingly tricky methods Thessaly the Hero had to employ to evade its gaze.

Blackbeard: OK, Blackbeard’s not a D&D monster, but he should be. He’s a definite Thessaly favorite and has escaped from prison nearly as many times as the tarrasque has. Blackbeard’s appearance on the scene has allowed me to expand the scope of the nightly stories to include oceanic scenarios.

Leviathan: I’m not sure if there’s a leviathan in D&D lore, but I needed an aquatic monster to follow up on the popularity of Blackbeard, and so was born the leviathan, watery sibling of the tarrasque. Frequently teams up with the tarrasque to menace society.

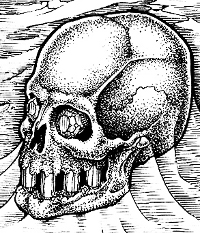

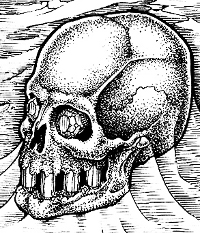

Yes, I know Acererak is technically a demi-lich, not a lich. I’m trying to keep things simple for my daughter until the day she grows up and learns the differences between types of undead wizard.

This was an attempt to introduce a wizardly villain into the stories. I described him as a “skeleton wizard,” which prompted twenty minutes of uncomfortable questions about how a skeleton could still be alive, what happens to people’s skin when they die, will deceased pets return as ambulatory skeletons, etc. Once I got through the existential grilling, I was able to establish Acererak (originally from

Tomb of Horrors) as a scheming wizard who can usually be tricked into falling into his own traps.

Cribbing bad guys from the Monster Manual has made me realize anew just how creative and entertaining many of the Monster Manual entries are; watching my daughter smile at the mental picture of a beholder or an umber hulk reminds me of what it was like to first flip through the pages of the AD&D Monster Manual as a kid.

With the variety of creatures in the Monster Manual—and the sheer number of monster books published over the years—I’m hoping this will last me until Thessaly tires of the format. And at this rate, I can tell several years’ worth of stories before I have to resort to incorporating the flumph….

by

by

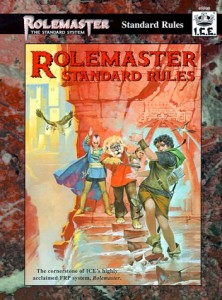

Hey, look! A new version of the vintage Rolemaster RPG is out, and they’ve released

Hey, look! A new version of the vintage Rolemaster RPG is out, and they’ve released