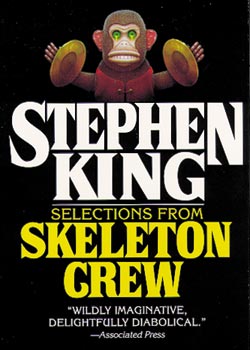

That’s our creepy little friend right there.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: Hal Shelburn was plagued throughout his childhood by the presence of a nightmarish cymbal-banging monkey toy; each time it clangs its cymbals, somebody close to Hal dies. Now an adult, he tries to find a way to get rid of it for good before it claims the lives of his wife and kids.

My thoughts: Oh, the cymbal-banging monkey, most terrifying of toys. It’s the perfect fit for the “evil childhood toy” horror trope, and occupies a spot of honor next to the creepy doll. I don’t know what prompted Stephen King to write a story based on one, but I’m guessing he spotted one of these things in an antique shop and just knew right then and there that it had to star in one of his stories.

“The Monkey” is a fairly long story and covers a surprising amount of narrative ground, given its premise. As a boy, Hal discovers the creepy, apparently broken monkey toy, but quickly realizes that when it clangs it cymbals (seemingly at random, once every couple years), somebody close to him dies—first a babysitter, then a childhood friend, and finally even his mother. Despite various attempts to get rid of it, the monkey always eventually re-appears. Now it’s re-appeared in his adult life, and he must scramble to banish it before it starts working its evil magic again.

A story premise like this is tricky to pull off, because it openly invites readers to imagine how they would go about destroying or getting rid of the cursed item. You’re almost certain to come up with a better plan than the story’s characters do; and even though you know that horror stories would be very boring if everybody did the smart, reasonable thing, it diminishes the story’s impact if you think the characters are behaving stupidly. That is somewhat the case here; although the story recounts numerous attempts to get rid of the monkey, it takes a very long time (years) and several deaths before those attempts become more serious than “I’ll just stick it back in its box in the closet.” I know, I know… Hal is a child; and the story states that the monkey finds a way to thwart every attempt to destroy or discard it… but I kept wanting somebody to at least try smashing it or tearing it apart rather than hiding it or throwing it down wells. Even as an adult, Hal inexplicably lets his family keep the monkey around for a day or so before doing anything about it.

So a little extra suspension of disbelief is required. Fair enough.

The real problem with “The Monkey” is that it’s just too long. It tells two stories in parallel: Hal’s troubles with the monkey in his childhood years, and Hal’s present-day, grown-up encounter with the same toy. There’s something powerful in forcing an adult protagonist to confront and relive the terrors of their imaginative youth, and King will use this theme to good effect in It and other novels. Here, however, it all just goes on too long. After about the sixth monkey-caused mysterious death, the concept has worn thin. There’s a good horror story in here, but it’s stretched across too many pages.

There are things that work well here, however. As usual, King’s depiction of family relationships (in this case, a fairly dysfunctional one) is great. Hal’s relationship with his two sons takes the spotlight—he loves his younger son dearly, but struggles to relate to his older, teenage son, who is going through a rebellious phase. King uses these father-son relationships to good effect; for most of the story, I was very nervous that King would kill off one of the sons (he doesn’t), and in that case I’m not sure I would’ve been able to finish reading this.

A random note: one other thing I noticed is King’s effective use of specific name brands where other authors would use generic terms. It’s not a box, it’s a Ralston-Purina box. It’s not a magazine, it’s a copy of Rock Wave. It’s not a tin, it’s a Crisco tin. It adds a certain grounded-ness to the story.

All in all, “The Monkey” is mediocre but not without its charms. If you’re in the mood for a scary-toy story this Halloween, I recommend firing up “Living Doll” instead.

Next up: “The Lawnmower Man,” from Night Shift.

My thoughts: This is a sweet, sad little story told in the form of a screenplay. Given the close association of King’s written work with film, it seems appropriate to find a King-written screenplay tucked in here amidst his more traditional short stories.

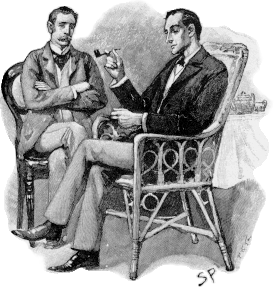

My thoughts: This is a sweet, sad little story told in the form of a screenplay. Given the close association of King’s written work with film, it seems appropriate to find a King-written screenplay tucked in here amidst his more traditional short stories. My thoughts: When Andy asked me to read Stephen King’s short story “The Doctor’s Case,” I was sure it would be too violent for me. I haven’t read anything by King since high school, but my vague recollections suggested to me that he wouldn’t be able to resist getting some gory details in some way or another. I was surprised to find that the extent of the gore consisted of the phrase “There was a dagger in his back.” I’m happy to say I rallied quickly from this assault upon my sensibilities.

My thoughts: When Andy asked me to read Stephen King’s short story “The Doctor’s Case,” I was sure it would be too violent for me. I haven’t read anything by King since high school, but my vague recollections suggested to me that he wouldn’t be able to resist getting some gory details in some way or another. I was surprised to find that the extent of the gore consisted of the phrase “There was a dagger in his back.” I’m happy to say I rallied quickly from this assault upon my sensibilities.  The story: “Trucks,” collected in Night Shift. First published in 1973.

The story: “Trucks,” collected in Night Shift. First published in 1973.  We never get an explanation for this automotive revolt, and the story doesn’t really need one. All we need to know is that every motor vehicle larger than a car is now possessed of a bloodthirsty cunning, and is working in coordination with other vehicles to kill us. The protagonists are a mostly forgettable collection of average Americans—a salesman, a trucker, a cook, some teenagers, and the anonymous narrator—and they follow the horror-survival script closely as they hunker in a diner, watching malevolent semi trucks circle the property. The salesman snaps and makes an ill-advised break for freedom (and dies badly); the narrator tries to rally the others to make longer-term survival plans. After a few more characters are killed, the true horror of the situation becomes clear: the trucks—implied now to have free reign across all of America, and whose ranks now include not only semis but construction vehicles, tractors, and possibly even aircraft—intend for the humans to be their slaves, refueling and maintaining the vehicles in exchange for their lives.

We never get an explanation for this automotive revolt, and the story doesn’t really need one. All we need to know is that every motor vehicle larger than a car is now possessed of a bloodthirsty cunning, and is working in coordination with other vehicles to kill us. The protagonists are a mostly forgettable collection of average Americans—a salesman, a trucker, a cook, some teenagers, and the anonymous narrator—and they follow the horror-survival script closely as they hunker in a diner, watching malevolent semi trucks circle the property. The salesman snaps and makes an ill-advised break for freedom (and dies badly); the narrator tries to rally the others to make longer-term survival plans. After a few more characters are killed, the true horror of the situation becomes clear: the trucks—implied now to have free reign across all of America, and whose ranks now include not only semis but construction vehicles, tractors, and possibly even aircraft—intend for the humans to be their slaves, refueling and maintaining the vehicles in exchange for their lives. So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently.

So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently.