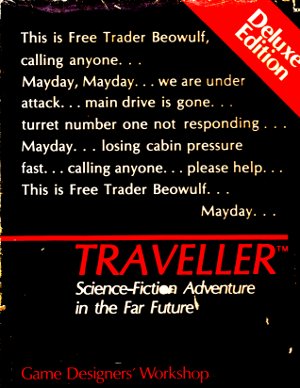

The story: “Trucks,” collected in Night Shift. First published in 1973. Wikipedia entry here.

The story: “Trucks,” collected in Night Shift. First published in 1973. Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synposis: A motley crew of individuals is besieged inside a roadside diner by a pack of semi tractors and other trucks, which have come to life and are seemingly intent on wiping out their human creators and masters.

My thoughts: This early King short story deals with a theme that is now very familiar to any science fiction fan: the machine revolution. In the years since this story was published, many successful books, stories, and movies have built on the idea that one day, the precious machines on which we rely so much (too much, they suggest) will turn on us.

These days, most such stories imagine that it is computers which will revolt, and that their ubiquity and deeply-layered networking will make them nearly unstoppable. “Trucks,” however, hails from a time before computers (as we think of them today) were the brains behind every complex mechanical or electronic gadget; this story is heir to the tradition of “haunted car” tales (a subgenre King returns to in his 1983 novel Christine).

We never get an explanation for this automotive revolt, and the story doesn’t really need one. All we need to know is that every motor vehicle larger than a car is now possessed of a bloodthirsty cunning, and is working in coordination with other vehicles to kill us. The protagonists are a mostly forgettable collection of average Americans—a salesman, a trucker, a cook, some teenagers, and the anonymous narrator—and they follow the horror-survival script closely as they hunker in a diner, watching malevolent semi trucks circle the property. The salesman snaps and makes an ill-advised break for freedom (and dies badly); the narrator tries to rally the others to make longer-term survival plans. After a few more characters are killed, the true horror of the situation becomes clear: the trucks—implied now to have free reign across all of America, and whose ranks now include not only semis but construction vehicles, tractors, and possibly even aircraft—intend for the humans to be their slaves, refueling and maintaining the vehicles in exchange for their lives.

We never get an explanation for this automotive revolt, and the story doesn’t really need one. All we need to know is that every motor vehicle larger than a car is now possessed of a bloodthirsty cunning, and is working in coordination with other vehicles to kill us. The protagonists are a mostly forgettable collection of average Americans—a salesman, a trucker, a cook, some teenagers, and the anonymous narrator—and they follow the horror-survival script closely as they hunker in a diner, watching malevolent semi trucks circle the property. The salesman snaps and makes an ill-advised break for freedom (and dies badly); the narrator tries to rally the others to make longer-term survival plans. After a few more characters are killed, the true horror of the situation becomes clear: the trucks—implied now to have free reign across all of America, and whose ranks now include not only semis but construction vehicles, tractors, and possibly even aircraft—intend for the humans to be their slaves, refueling and maintaining the vehicles in exchange for their lives.

This is a difficult scenario for King to sell, and the story works best if you just don’t think about it too much. The two obvious problems in the trucks’ plan are the simple facts that humans are a) massively numerous and b) able to take refuge in all sorts of places where the trucks can’t go. King anticipates these points and has the narrator reflect that, given time, there are few places on the planet that determined machines could not level, pave, destroy, or reach. I can accept that for the sake of the story, but the implausibility of the scenario keeps “Trucks” from being as tense or scary as horror stories with more… versatile threats.

Of course, King is using this scenario to make an ecological lament: the protagonist’s realization that no refuge remains on Earth that cannot be wrecked by our machines is a critique of urban sprawl and the encroachment of our fuel-guzzling, air-polluting civilization on what was once an open-ended wilderness. And there’s also the suggestion that we’ve become so reliant on our machines and technology that we’re effectively enslaved to it. (This is a point that resonates well in our world of cellphones and social networks.)

Ultimately, “Trucks” is an entertaining but mostly forgettable story. The protagonists don’t do, say, or think anything memorable, and the concept of technology turning on its creator is now such a common plot device that this story comes across as quaint, rather than terrifying.

Next up: “The Road Virus Heads North,” from Everything’s Eventual.

So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently.

So then: Richard Hagstrom receives a mysterious word processor from his nephew (who was shortly thereafter killed in a car accident caused by his drunken father, Richard’s brother). Richard hides in his study from his shrewish wife (whose obesity King uncomfortably counts as a further moral mark against her, something I suspect he wouldn’t write today) and bratty, disrespectful teenage son. After playing with the word processor a bit, he figures out that he can change reality by typing or deleting sentences with the machine. He also learns that, like the wish-granting genie’s lamp of legend, the word processor will only afford him a handful of “wishes” before it stops working, presumably permanently. Spoiler-filled synopsis: A man diagnosed with terminal cancer makes a deal with the devil: he’ll get better if he designates somebody else who will suffer in his place. He designates his “best friend,” whom he secretly hates, and enjoys a long, healthy life while his friend’s life falls apart.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A man diagnosed with terminal cancer makes a deal with the devil: he’ll get better if he designates somebody else who will suffer in his place. He designates his “best friend,” whom he secretly hates, and enjoys a long, healthy life while his friend’s life falls apart.

But moving along: after wandering lost a while (this story takes place before cellphones and GPS devices were commonplace or even imaginable), the two stumble across a picturesque, nostalgic little all-American town with the cutesy name of “Rock and Roll Heaven,” planted inexplicably in the middle of a huge creepy forest wilderness. King often allows his protagonists a certain meta-awareness of their horror-story plights; Mary immediately recognizes that the too-perfect town is creepy as heck, and even mentions its evocation of Twilight Zone episodes and Ray Bradbury stories.

But moving along: after wandering lost a while (this story takes place before cellphones and GPS devices were commonplace or even imaginable), the two stumble across a picturesque, nostalgic little all-American town with the cutesy name of “Rock and Roll Heaven,” planted inexplicably in the middle of a huge creepy forest wilderness. King often allows his protagonists a certain meta-awareness of their horror-story plights; Mary immediately recognizes that the too-perfect town is creepy as heck, and even mentions its evocation of Twilight Zone episodes and Ray Bradbury stories. Every year when Halloween looms on the horizon, I find myself in the mood for scary stuff. In past Octobers, I’ve made a point of watching horror movies, playing horror-themed boardgames, or reading spooky books.

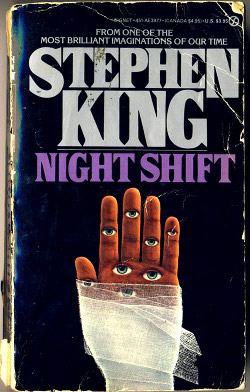

Every year when Halloween looms on the horizon, I find myself in the mood for scary stuff. In past Octobers, I’ve made a point of watching horror movies, playing horror-themed boardgames, or reading spooky books.