The story: The Langoliers, collected in Four Past Midnight. First published in 1990. Wikipedia entry here.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A handful of passengers on a red-eye flight across America wake up to find that the rest of the passengers—and the plane’s crew—have vanished into thin air. They manage to land the plane (one of the group is a pilot), only to find that the world is gray and dead—they have gone back in time, but it turns out the past is an empty shadow of the present. And strange creatures called the langoliers, who “tidy up” history by literally devouring the past, are headed their way.

Spoiler-filled synopsis: A handful of passengers on a red-eye flight across America wake up to find that the rest of the passengers—and the plane’s crew—have vanished into thin air. They manage to land the plane (one of the group is a pilot), only to find that the world is gray and dead—they have gone back in time, but it turns out the past is an empty shadow of the present. And strange creatures called the langoliers, who “tidy up” history by literally devouring the past, are headed their way.

My thoughts: The Langoliers was the story that launched my decades-long Stephen King obsession.

I was in late high school (so 1992 or thereabouts) when my mom came home from the library with a copy of Four Past Midnight. I had never read anything by Stephen King before, and in fact viewed him with faint suspicion and distaste. To this day I’m not sure what led my mom to pick up that book for me from the library, but I’m glad she did.

I read two of the four novellas in Four Past Midnight before the book had to be returned to the library: The Langoliers and The Sun Dog. I don’t recall which one I read first, but I know that while The Sun Dog left little impression on me, The Langoliers absolutely blew my mind. I’d never read anything quite like it in all my years of voracious reading. I went on to read The Stand, followed by It, and by then my addiction was real.

All this to say that I’ve both looked forward to, and dreaded, returning at last to The Langoliers, which I never revisited after my initial reading. Like most of the King stories I read in the early days of my King addiction, it sits atop a very high pedestal; and I’ve often wondered if it really was that good, or if that’s just the nostalgia talking. (Some of the King novels I’ve re-read, such as The Stand, have lived up to their reputation and my own memories. Others, like It, proved disappointing on a re-read.)

So how is The Langoliers? It’s not as mind-bogglingly good as I remember, but it’s not bad, either. The setup is excellent: a motley crew of airline passengers trapped on a plane, all dropped into the deep end of a seemingly impossible mystery. They’re up against two threats: an external threat in the form of the “langoliers,” reality-devouring monsters who “clean up” the past; and an internal threat in the form of one of their own number, who is deeply, homicidally crazy.

When this novella was first published in 1990, I suspect that the piece of pop culture it called most immediately to mind was one of two Twilight Zone episodes: “The Odyssey of Flight 33,” in which a commercial airliner travels into the past, or possibly “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet”—two classic uses of air travel as a horror-suspense setting. But a modern reading of The Langoliers evokes instead evangelical Rapture fiction, notably the execreble Left Behind series… which also features a handful of passengers discovering that everybody else on the plane has vanished, leaving behind a scattering of clothes, false teeth, purses, and other uncomfortably intimate items. But The Langoliers predates Left Behind, if not the dispensationalist obsession with the Second Coming; and as the passengers discuss the meaning of what’s happened, nobody ever mentions the Rapture as a possibility.

What follows is 200 pages of competent suspense (not horror, really) storytelling. The surviving crew contains the usual assortment of stock characters ranging from the mundane (The Coming of Age Kid, The Writer) to the somewhat ridiculous (the British Secret Agent), and each of the characters gets their chance to shine at some point in the narrative. Most of the action takes places on the ground, once the group manages to land their plane; alone in a completely empty and lifeless airport, they use clues in the environment to deduce (with implausible accuracy) the nature of their predicament, and figure out a way to get the plane airborne again and back through the time-warp that brought them here. It’s at this point that the crazy guy (a well-written example of the Insane Psycho, a staple Stephen King character) strikes, and also that the heroes get their first glimpse of the rapidly-approaching, all-consuming langoliers. A redshirt character dies, a few Noble Sacrifices take place, the bad guy gets what’s coming to him, and the heroes finally escape back into the present time.

The Langoliers is competent, but strangely for its relatively short length, actually comes close to dragging at points. I have no way of knowing if this is true, but I get the feeling when reading King novels from the mid-1980s through the mid-1990s that somewhere during this period, King’s editors stopped doing much to reign in King’s verbose tendencies. In The Langoliers, as in It and other novels from this era, King belabors routine sequences, lets slips some cringeworthy dialogue (“Now I find myself involved in a mystery a good deal more extravagant than any I would ever have dared to write,” says the writer character at one point) and gets a bit too maudlin when handling emotional scenes. It’s not unenjoyable, but it’s Stephen King at his “safest.” The only glimmers of good ol’ Stephen King viciousness are found in the excellent sequences told from the viewpoint of the doomed, unsettlingly sympathetic psycho character.

This is good stuff. But it also feels like Stephen King on cruise control; The Langoliers is caught awkwardly between the cutthroat intensity of King’s early novels and the more mature reflection of his later work.

A closing note: The Langoliers is generally referred to as a novella, although at 230 pages I’m not sure why we don’t just consider it a regular-length novel. My guess is that by the late 1980s, King’s legendary writing pace had produced a backlog of novels awaiting release, so his publisher packed the four shortest manuscripts into an anthology and called it Four Past Midnight.

Next up: “Battleground,” in Night Shift.

My thoughts: Another vampire story! “One for the Road” is best read as an epilogue to the (excellent) vampire novel ‘Salem’s Lot; without that context, it loses much of its impact. Whether or not you read it in connection with that novel, however, this is a short, simple story that belongs to the “Want to hear about something spooky that happened to me?” around-the-campfire genre. It all builds to the vampire encounter in the final pages—a conclusion that is telegraphed from the story’s opening pages but is nonetheless creepy and tense when it unfolds.

My thoughts: Another vampire story! “One for the Road” is best read as an epilogue to the (excellent) vampire novel ‘Salem’s Lot; without that context, it loses much of its impact. Whether or not you read it in connection with that novel, however, this is a short, simple story that belongs to the “Want to hear about something spooky that happened to me?” around-the-campfire genre. It all builds to the vampire encounter in the final pages—a conclusion that is telegraphed from the story’s opening pages but is nonetheless creepy and tense when it unfolds. My thoughts: As I’ve

My thoughts: As I’ve  My thoughts: Stephen King writes good vampire stories. I sometimes think it’s a shame he doesn’t write more of them.

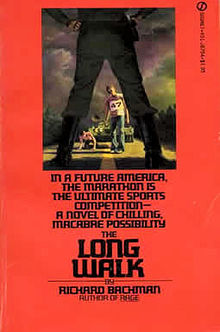

My thoughts: Stephen King writes good vampire stories. I sometimes think it’s a shame he doesn’t write more of them. My thoughts: Like Stephen King’s other early “Bachman” novels, The Long Walk is not a supernatural or traditional horror story.It is instead a precursor of the “teen dystopia” genre dominated today by the Hunger Games books. Set in an alternate-history modern America, The Long Walk follows the teenaged participants in a gruesome national pastime: a walking marathon that ends when only one walker is left standing.

My thoughts: Like Stephen King’s other early “Bachman” novels, The Long Walk is not a supernatural or traditional horror story.It is instead a precursor of the “teen dystopia” genre dominated today by the Hunger Games books. Set in an alternate-history modern America, The Long Walk follows the teenaged participants in a gruesome national pastime: a walking marathon that ends when only one walker is left standing. At its heart, this is a story about the sacrifices a mother makes for the sake of her child. Martha, the protagonist, is a poor black woman married to an abusive thug during the Civil Rights era. Pregnant, confused and desperate, she seeks out the counsel of a

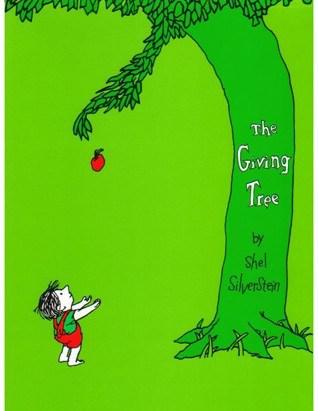

At its heart, this is a story about the sacrifices a mother makes for the sake of her child. Martha, the protagonist, is a poor black woman married to an abusive thug during the Civil Rights era. Pregnant, confused and desperate, she seeks out the counsel of a

My thoughts: There are a lot of ways you can doom yourself in a horror story. You might decide to descend alone into the lightless basement to check the circuit breaker. You might lean forward to examine the “dead” monster at extremely close range, because it’s dead and there’s no way it poses any danger to you. And here’s another way you can telegraph your impending death: scoff derisively at people who insist that an object is cursed and that you should stop messing with it.

My thoughts: There are a lot of ways you can doom yourself in a horror story. You might decide to descend alone into the lightless basement to check the circuit breaker. You might lean forward to examine the “dead” monster at extremely close range, because it’s dead and there’s no way it poses any danger to you. And here’s another way you can telegraph your impending death: scoff derisively at people who insist that an object is cursed and that you should stop messing with it.